Impressions of a Foreign Critic

Reflections on Hong Kong/Taiwan cinema, and especially the future of the Mandarin-dialect industry, after a visit to Taiwan and the Golden Horse Awards in Oct-Nov 1980.

To the Western critic the film industries of Hong Kong and Taiwan present an enviable sight: industrious, productive and possessed of a distinct cultural identity. And what is perhaps most attractive to the jaded foreign critic is Hong Kong/Taiwan cinema’s resolute assertiveness, a bright (often brash) positiveness which Western cinema also enjoyed during the 1950s and 1960s but which it is only just beginning to rediscover after a decade of introversion and doubt.

To the Western critic the film industries of Hong Kong and Taiwan present an enviable sight: industrious, productive and possessed of a distinct cultural identity. And what is perhaps most attractive to the jaded foreign critic is Hong Kong/Taiwan cinema’s resolute assertiveness, a bright (often brash) positiveness which Western cinema also enjoyed during the 1950s and 1960s but which it is only just beginning to rediscover after a decade of introversion and doubt.

It was this quality which first attracted me, like several other Western critics, to Hong Kong/Taiwan cinema when the martial-arts boom first hit London in 1973. It rekindled my dormant interest in the Chinese language and culture and provided a point of focus for reviving that interest. During the past eight years or more, it has led me on a labyrinthine journey through one of the world’s liveliest film industries which, even now, many hundreds of films and many thousands of words later, I still feel only on the verge of discovering.

It became clear early on that it was necessary to learn Chinese in order to full get to grips with this phenomenon. The little material provided in English was either misleading or a confusing mass of garbled names and information. It was also necessary to see Chinese-language versions of the films – in London’s thriving Chinatown cinemas – rather than the execrable dubbed versions circulating in popular cinemas. There opened up a world far beyond the martial-arts film: the literary period extravaganzas of Li Hanxiang 李翰祥; the wenyi pian 文艺片 of Li Xing 李行, Bai Jingrui 白景瑞; the Cantonese comedies of Xu Guanwen 许冠文 [Michael Hui]; the immaculate period pieces of Hu Jinquan 胡金铨 [King Hu]; and the varied works of directors like Chen Yaoqi 陈耀圻 [Richard Chen], Ding Shanxi 丁善玺, Song Cunshou 宋存寿, Gao Baoshu 高宝树, Liu Jialiang 刘家良, Chu Yuan 楚原, Sun Zhong 孙仲, Tu Zhongxun 屠忠训, etc.

On closer inspection, Hong Kong/Taiwan cinema of course has its troubles like any other industry. The present problems of Mandarin[-dialect] cinema in the face of the re-birth of Cantonese[-dialect] cinema – and the strong identity of the so-called Hong Kong New Wave – represent a major challenge to Taiwan cinema in particular. The Hong Kong and Taiwan cinemas, despite being bound by common economic ties and talent, seem more and more to be strangers amid a shared Chinese heritage: the wenyi pian which thrived during the 1970s seem threatened during the 1980s; the wuxia pian 武侠片 and gongfu pian 功夫片, which have been undergoing every kind of transformation for the past 15 years, have asserted different Cantonese and Mandarin identities; the war dramas of Taiwan would seem to hold little interest for audiences elsewhere.

After eight years of studying and writing about the Hong Kong/Taiwan industries, I had my first chance to visit the East in Oct-Nov 1980, as guest of the 17th Golden Horse Awards 金马奖. Taiwan and its culture held few surprises after such a long period of preparation! The only surprise was the sheer depth of hospitality extended by friends and acquaintances and the surprise of everyone that a foreign critic should even be interested in – let alone knowledgeable about – their film-making activities! The main value of the trip was to meet in person many of the people involved and hear their own opinions first-hand: their doubts and aspirations, and their enquiries as to how their films were received in the West.

The relatively low budgets (by Western standards) and the uncaring attitudes of most producers have forced many directors to mark time during their careers with commercial works unworthy of their talents. Several famous directors spoke of their wish to film historical, literary subjects which they at present were unable to raise the money for; other younger directors are frustrated by the difficulties of entering an industry which they consider dominated by a handful of top, commercial names monopolising the available capital.

These problems are not special to Taiwan, though there has so far been no New Wave of ex-TV directors like recently in Hong Kong (Xu Anhua 许鞍华 [Ann Hui], Xu Ke 徐克 [Tsui Hark], Tan Jiaming 谭家明 [Patrick Tam], Yan Hao 严浩 [Yim Ho], etc.). Hopefully a Taiwan New Wave will soon emerge – and composed of directors like Pan Rongmin 潘榕民 who wish to work within the values of Chinese culture, rather than like some of the young Hong Kong directors whose cultural identities boil down into a bland internationalism. Taiwan’s strong identity as a promoter of traditional Chinese values in a modern world should be used to its advantage in building an industry with international, rather than merely local, recognition. [Within a year or so of writing this, a Taiwan New Wave did start to emerge, though not from TV. It was largely led by young directors who had studied film in the US. Pan was not among them.]

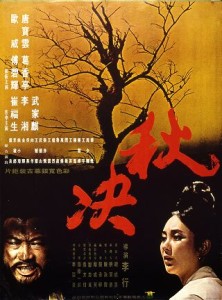

There is no shortage of talent; merely a lack of its proper organisation and exploitation. Why has it been so long since Li Xing produced a masterpiece like Execution in Autumn 秋决 (1972, see poster, left), Song Cunshou one like The Dawn 破晓时分(1968) or Ghost of the Mirror 古镜幽魂 (1974), Bai Jingrui one like Goodbye, Darling 再见阿郎 (1970)…? Why did Chen Yaoqi’s masterly The Pioneers 源 (1980) have to be released in a short version, like Hu Jinquan’s Legend of the Mountain 山中传奇 (1979)? It is not simply a problem of providing talented directors like Li, Song, Bai, Chen and others with the necessary money to make worthwhile films; it is also a problem of educating both the public and film producers.

There is no shortage of talent; merely a lack of its proper organisation and exploitation. Why has it been so long since Li Xing produced a masterpiece like Execution in Autumn 秋决 (1972, see poster, left), Song Cunshou one like The Dawn 破晓时分(1968) or Ghost of the Mirror 古镜幽魂 (1974), Bai Jingrui one like Goodbye, Darling 再见阿郎 (1970)…? Why did Chen Yaoqi’s masterly The Pioneers 源 (1980) have to be released in a short version, like Hu Jinquan’s Legend of the Mountain 山中传奇 (1979)? It is not simply a problem of providing talented directors like Li, Song, Bai, Chen and others with the necessary money to make worthwhile films; it is also a problem of educating both the public and film producers.

Many times in Taiwan I was asked, as a foreign critic, what I thought were the main problems with Chinese cinema being accepted abroad. I replied there were four technical problems: (1) poor English subtitling, (2) the tradition of dubbing actors’ voices, (3) the perspective-less dubbing of sound, and (4) an over-reliance on songs, the zoom lens, and restless editing. The greatest directors are able to rise above these technical problems, especially when both script and actors are of sufficient quality, but it would be as well to tackle the problems head-on. Chinese directors and craftsmen have a highly-developed visual sense. It is time for this to be marshalled and be shared with international audiences through the medium of cinema.

Some of the works of Hu Jinquan, Li Hanxiang, Li Xing and others have been seen at international festivals. More must be seen – regularly – if Chinese cinema is to gain an identity. The Golden Horse Awards could also play a part here by providing an international focus for the Taiwan industry. Until the present it has mostly been a localised event, unknown outside the Far East. In 1980 I saw, however, a definite desire by several people to broaden the Awards’ horizon – to create a genuine Taiwan Film Festival, complete with an International Section as well as Domestic Awards Ceremony. It is vital that this transformation should take place – and be recognised by the international film community and by foreign critics – if Mandarin cinema is ever to build an international reputation from which, like Japanese cinema’s, it can mutually benefit.

(Originally published in Chinese and English in Hong Kong monthly CinemArt 银色世界, Feb 1981 [No. 134]. Modern annotations in square brackets.)