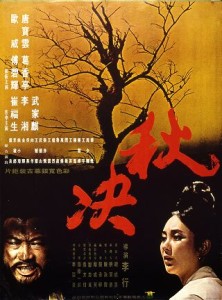

Execution in Autumn

秋决

Taiwan, 1972, colour, 2.35:1, 99 mins.

Director: Li Xing 李行.

Rating: 9/10.

A moving costume drama of love and spiritual regeneration, exquisitely told and acted.

Early Western Han dynasty, 2nd century BC, somewhere in northern China. The combustible Pei Gang (Ou Wei), last surviving male of the noble Pei family, is sentenced to death for the murder of a young woman, Chuntao (Li Xiang), and her two accomplices after flying into a rage following their claim that he was the father of her child. Pei Gang’s domineering, over-protective grandmother (Fu Bihui), afraid the family line will die out, tries various ruses to get her grandson freed; but Pei Gang is unrepentant at his trial. As it has been decreed that executions can only take place in autumn, and the season has just passed, Pei Gang has to wait a year for the sentence to be carried out. An official whom the grandmother has bribed suggests that, if Pei Gang marries while in prison, he will at least be able to ensure the family line continues. The grandmother asks a ward of the family, Lian’er (Tang Baoyun), to perform this duty, and manages to persuade the prison head (Ge Xiangting) to let her visit Pei Gang. However, Pei Gang refuses to go along with the idea, unwilling to make Lian’er a widow. Meanwhile, Pei Gang has been going through a transformation in his outlook on life, prompted first by a thief (Chen Huilou) he gets to know in the prison and then by a scholar (Wu Jiaqi) who turns him towards Daoism. The prison head also starts to develop a respect for the changed Pei Gang.

REVIEW

It was the Electric Cinema [a repertory house in north London], a year or so ago [in early 1975], that gave non-specialists [in the UK] a chance to see high quality Chinese cinema in the original language and complete: The Fate of Lee Khan 迎春阁之风波 (1973) by Hu Jinquan 胡金铨 [King Hu]. With Hu now better established here – A Touch of Zen 侠女 (1970-73) screened at last year’s London Film Festival [in Dec 1975] and is now with a commercial distributor along with his latest picture, The Valiant Ones 忠烈图 (1975) – the Electric tries again, this time with a double bill which shows the smug West that there is more to Chinese cinema than martial arts: Execution in Autumn 秋决 by Li Xing 李行, plus Blood Reincarnation 阴阳界 (1974) by Ding Shanxi 丁善玺, a trilogy of Chinese ghost stories by one of Taiwan’s most successful serio-comic directors.

Li, however, is in every way the more experienced and accomplished of the two Taiwan directors. His earliest [Mandarin-dialect] work dates from 1963, and he is well regarded in the East, both for his thoughtful approach to a variety of highly commercial subjects and his interest in Chinese mores. His subjects can range from run-of-the-mill star vehicles like The Wedding 婚姻大事 (1974), an elaborate confection for Zhen Zhen 甄珍 and Qin Xianglin 秦祥林 raised far above the ordinary, to strident anti-Japanese melodramas like Land of the Undaunted 吾土吾民 (1975); Execution in Autumn shows an altogether softer line, more in content than direction (Li’s style rarely rises to the hysterical), and this time places its central love story not in a comic or nationalist context, but a philosophical one.

The time is Han dynasty China (206 BC – AD 220), an early period which saw many new developments, chiefly towards greater bureaucratic and social complexity, in China’s history. An introduction tells us that autumn was the traditional time decreed for executions, and we next see a desperate prisoner on the run. It is autumn now, and during the prisoner’s cursory trial flashbacks show us how he was blackmailed by a girl, Chuntao, and her associates who claimed he was the father of her child; in a rage Pei Gang, the prisoner, killed both her and her two accomplices. Pei loses his case and is committed to prison to await the order of execution: while there, with his ageing grandmother fighting for his release outside, he undergoes a profound philosophical change in outlook, both through his contact with two other prisoners and his relationship with a girl who marries him in prison to ensure the continuation of the family line. When, next autumn, the decree arrives from the capital, its message is almost immaterial…

The theme has many echoes in the American cinema, not least I Want to Live! (1958) and Birdman of Alcatraz (1962). Li, however, goes several steps deeper, and makes full use of his period setting beyond its obvious backdrop effect. The story has many concurrent threads and it is a measure of the extraordinarily well-written script by Zhang Yongxiang 张永祥 that each contains specific resonances of Han dynasty China. The period was something of a melee of many philosophies, not necessarily conflicting and certainly responsible for the great vigour of its artistic life: Confucianism officially reigned supreme, but the forces of Daoism and the basic Chinese principle of the forces of yin and yang exerted powerful influence. The yin/yang idea was also bound up with the notion of the five elements, and the film’s structure can be seen to stem from this. The guiding course of nature (also a Daoist principle) overlooks everybody’s lives, and in the case of Pei actually determines the length: the film starts in autumn, with bare trees, fallen leaves, and russet tones, passes through winter with its snow, arrives in spring with its flowers and flowing water (significantly the time of Pei’s major change, marked by the Daoist ideal of water), and finally ends with the advent of a new autumn. Pei’s upbringing has been solidly Confucian (a flashback shows the over-protective nature of his grandmother’s relationship) and unwittingly he has been rebelling against it all along. The film essentially shows his progress towards a purer Daoist way of thought as a means of reconciling his hatred of the past with his natural filial duties: his relationship with his grandmother is equivocal, to say the least – her concern is motivated as much by the fact that Pei is the family’s only male heir as by her genuine love for him, and it is only with the arrival of spring and the chance news that she is dead that Pei eventually releases the pent-up frustrations of a lifetime (shouting “She never beat me!” as he pounds his chest with his manacled hands). This cathartic outcry against the resolute order, propriety and duty of Confucianism (even when dying his grandmother orders that her death be kept a secret from Pei so that he might die believing she was still fighting for his release) is the turning point in Pei’s future development.

His two fellow-prisoners each play their parts before they go their separate ways: the Thief advocates a carpe diem outlook when Pei is at his most beleaguered and irate, and is soon gone; the Scholar provides the biggest push towards Daoism and its acceptance of death and the cycle of things (“Never take life seriously…people are born and die every day”). It is, however, the girl Lian’er who completes the transformation – as is proper in even a sophisticated love story. It is in this relationship that the yin/yang conflict works most decisively: in his early days of imprisonment, Pei is very much the embodiment of the positive life-force (yang) – which implies no moral qualification – rebellious, irascible and determined to be free. Lian’er (“Lotus Child”), the embodiment of self-sacrifice, agrees to marry Pei in prison and bear his child; this callous, but entirely logical, plan by the grandmother is hatched without Pei’s knowledge, and, expectedly, he rejects Lian’er when she arrives. From hereon, the plot elements begin to coalesce: Pei rejects Lian’er when he realises she has only come because his family outside have given up hope (in fact, the venality of the growing Han bureaucratic system has worked against them) and rightly stresses that he could not care less about the family line once he is dead. The rejection has two important consequences: Pei’s life-force withers into a doomed introversion, and the grandmother, who has been waiting outside the prison in the snow, contracts the pneumonia which leads to death. Further subtleties are grafted on: the grandmother dies thinking that Lian’er carries Pei’s child, and her own death is for many months hidden from Pei himself.

Lian’er soon returns, and, without telling Pei that his grandmother is dead, talks him into marriage and bed. With the arrival of February, and spring, Lian’er has now settled into a routine of caring for Pei in prison (feeding him, tending his shackled ankles, and so on) and regenerating the broken portions of his personality into a more perfectly balanced whole by dint of her own personality. The Scholar is freed, and Pei is left alone in the prison, overseen by the ageing prison chief who is slowly growing to respect the new Pei (a likeness between Pei and his son also provides a more direct reason). With the arrival of the spring rains and their liberating force when Pei hears of his grandmother’s death from a warder, the equation is complete, and the countdown to the arrival of the order casts a shadow over the couple’s now-genuine happiness.

It says much for Execution in Autumn that the extremely complex philosophical underpinnings never find explicit mention in the script, despite the fact that it is from them that the film draws its incredible power. This is a love story, a tale of spiritual regeneration, on a very high plane, exquisitely told and acted and placed in an entirely appropriate setting. The entire picture is studio-shot, a very positive hindrance when one considers the vastness conjured up and the storybook effect of the whole, and the art direction [by Zou Zhiliang 邹志良] is particularly refreshing. The Han era is not the most common setting for Chinese period films, and the attention paid to details like Han ware and interior architecture is a constant delight. In such controlled conditions Li Xing is able to paint some devastating canvases: the snowy scenes of Lian’er’s arrival at the prison, cloaked against the cold and in wedding apparel (to a lyrical accompaniment of oboe, strings and harp) and her eventual departure when it has stopped snowing, are most beautifully realised; and the several montages of the pair in prison (particularly the unbearable stillness of their last night together), again in combination with the softly chordal, surging, Maurice Jarre-ish score by [Japanese composer] Saito Ichiro 齐藤一郎, are tremendously moving. It is here, in the final reels, that Li’s stress on the claustrophobia of their existence pays off: the elegant screens of the family home find reflection in the cruder wooden bars of the prison cells, and Lian’er and Pei’s final dreams of freedom are particularly eloquent against this setting. The two principals, both well-known Taiwan players (though actress Tang Baoyun 唐宝云, who went to America soon after and has only just returned, is not currently making any more films), must take much of the credit for the film’s success, and among the supporting parts one must single out Ge Xiangting 葛香亭 as the prison governor, a past-master at playing this sort of role. With a work of this quality available, Chinese cinema has gained a powerful ally in gaining a separate identity from the Japanese monopoly. Badger your local exhibitor to screen it.

CREDITS

Produced by Ta Chung Motion Picture (TW).

Script: Zhang Yongxiang. Photography: Lai Chengying. Editing: Chen Hongmin. Music: Saito Ichiro. Art direction: Zou Zhiliang. Costume design: Wang Wenwei. Costumes: Shu Lanying. Sound: Wang Rongfang, Jiang Sheng, Huang Jinzhi. Action: Chen Huilou.

Cast: Tang Baoyun (Lian’er), Ou Wei (Pei Gang), Ge Xiangting (prison head), Fu Bihui (grandmother), Wu Jiaqi (scholar), Li Xiang (Chuntao), Cui Fusheng (country magistrate), Han Su (Pei Shun), Zhou Shaoqing (Cao, criminal), Wang Yu (second lord), Chen Huilou (thief), Chen Jiu, Wang Fei, Min Min (prison guards), Wan Jie, Wang Yun (attendants), Lu Zhi, Li Minlang (brawny men), Yang Lie, Wang Hanchen (condemned prisoners), Xiang Yang (farmer), Wu Yan (farmer’s wife), Jin Hui (boy), Yao Xiaozhang (married woman).

Release: Taiwan, 14 Feb 1972.

(Review section originally published in UK monthly films and filming, Aug 1976. Modern annotations in square brackets.)