Fantasies behind the Pearly Curtain:

Hong Kong Cinema in Perspective

An introduction to Hong Kong/Taiwan cinema, written in 1977, five years after its breakthrough in the West.

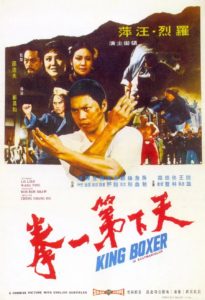

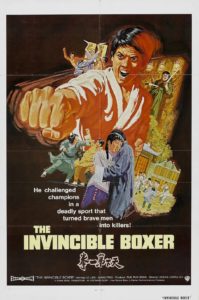

The breakthrough came at Cannes in [May] 1972, where two Hong Kong film companies, Shaw Brothers 邵氏兄弟 and Golden Harvest 嘉禾 (the latter through its distributor the Cathay Organisation), caused a minor stir by screening a selection of their product in the Market: interest was aroused and finally, after trying to attract Western distributors since the mid-1960s, Shao Yifu 邵逸夫 [Run Run Shaw] succeeded in selling a costume action drama [directed by South Korean contractee Jeong Chang-hwa 정창화 | 郑昌和] under the title The Invincible Boxer to Warner Brothers. [The film, known as King Boxer 天下第一拳 in Hong Kong, had just finished its run and taken a middling HK$761,000.] Retitled Five Fingers of Death in the US and using its original title in the UK, it had a sudden and amazing impact. In [central] London at the Warner, Leicester Square, it took £42,000 in two months; Cathay soon responded with a modest GH fight picture called Fist of Fury 精武门 (1972), starring a certain Li Xiaolong 李小龙 [Bruce Lee], which [had opened in Hong Kong a month before King Boxer and become the hit of the year, taking HK$4.4 million. It]

The breakthrough came at Cannes in [May] 1972, where two Hong Kong film companies, Shaw Brothers 邵氏兄弟 and Golden Harvest 嘉禾 (the latter through its distributor the Cathay Organisation), caused a minor stir by screening a selection of their product in the Market: interest was aroused and finally, after trying to attract Western distributors since the mid-1960s, Shao Yifu 邵逸夫 [Run Run Shaw] succeeded in selling a costume action drama [directed by South Korean contractee Jeong Chang-hwa 정창화 | 郑昌和] under the title The Invincible Boxer to Warner Brothers. [The film, known as King Boxer 天下第一拳 in Hong Kong, had just finished its run and taken a middling HK$761,000.] Retitled Five Fingers of Death in the US and using its original title in the UK, it had a sudden and amazing impact. In [central] London at the Warner, Leicester Square, it took £42,000 in two months; Cathay soon responded with a modest GH fight picture called Fist of Fury 精武门 (1972), starring a certain Li Xiaolong 李小龙 [Bruce Lee], which [had opened in Hong Kong a month before King Boxer and become the hit of the year, taking HK$4.4 million. It]  promptly broke every house record at the [Leicester Square cinema] Rialto (less than 600 seats) and established the diminutive but spunky Li as the first Oriental superstar. The words “kung-fu” (gōngfu 功夫, which means “skill” or “technique”) and “martial arts” began to enter filmgoers’ vocabulary, and the floodgates opened: The Killer 大杀手 (1972), The New One-Armed Swordsman 新独臂刀 (1971), Hap Ki Do 合气道 (1972), The Big Boss 唐山大兄 (1971), Enter the Dragon 龙争虎斗 (1973), The Way of the Dragon 猛龙过江 (1972), Chinese Vengeance 刺马 (1973, HK: The Blood Brothers), Intimate Confessions of a Chinese Courtesan 爱奴 (1972)… The boom continued through 1973, reached its climax in 1974 with the release of the rest of the Li films, began to show signs of strain in 1975 as more and more rubbish was quickly sold to unsuspecting distributors, and petered out in 1976 in a wave of re-issues and double bills. The irony of the situation, as far as the West is concerned, is that only a couple of months after Fist of Fury established Li as the major spearhead in the English-language market breakthrough, Li himself was dead – in Hong Kong, of acute cerebral oedema, on 20 Jul 1973, at the age of 32.

promptly broke every house record at the [Leicester Square cinema] Rialto (less than 600 seats) and established the diminutive but spunky Li as the first Oriental superstar. The words “kung-fu” (gōngfu 功夫, which means “skill” or “technique”) and “martial arts” began to enter filmgoers’ vocabulary, and the floodgates opened: The Killer 大杀手 (1972), The New One-Armed Swordsman 新独臂刀 (1971), Hap Ki Do 合气道 (1972), The Big Boss 唐山大兄 (1971), Enter the Dragon 龙争虎斗 (1973), The Way of the Dragon 猛龙过江 (1972), Chinese Vengeance 刺马 (1973, HK: The Blood Brothers), Intimate Confessions of a Chinese Courtesan 爱奴 (1972)… The boom continued through 1973, reached its climax in 1974 with the release of the rest of the Li films, began to show signs of strain in 1975 as more and more rubbish was quickly sold to unsuspecting distributors, and petered out in 1976 in a wave of re-issues and double bills. The irony of the situation, as far as the West is concerned, is that only a couple of months after Fist of Fury established Li as the major spearhead in the English-language market breakthrough, Li himself was dead – in Hong Kong, of acute cerebral oedema, on 20 Jul 1973, at the age of 32.

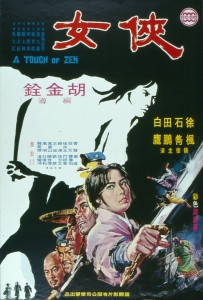

It is somehow typical of the whole situation that the West’s appreciation of Hong Kong’s biggest star should be posthumous. There is an after-the-event strain running right  through the saga which shows just how separate the European and East Asian industries are, and it is only now [in 1977], after the popular box-office boom has died, that a serious re-assessment is taking place of the industry which provoked it. Largely thanks to the director Hu Jinquan 胡金铨 [King Hu], whose A Touch of Zen 侠女 (1970-73) attracted the attention of critics (at Cannes in 1975) who had sneered at other Chinese product, the smug West has been forced to a certain extent to take notice of the vast repository of talent at work in Hong Kong and Taiwan: even now, however, merely a handful of critics are prepared to consider the films in anything other than sub-Japanese terms, and one doubts whether the impetus provided by Hu’s films (which are not typical of the mainstream) is strong enough to catapult other names to equal prominence.

through the saga which shows just how separate the European and East Asian industries are, and it is only now [in 1977], after the popular box-office boom has died, that a serious re-assessment is taking place of the industry which provoked it. Largely thanks to the director Hu Jinquan 胡金铨 [King Hu], whose A Touch of Zen 侠女 (1970-73) attracted the attention of critics (at Cannes in 1975) who had sneered at other Chinese product, the smug West has been forced to a certain extent to take notice of the vast repository of talent at work in Hong Kong and Taiwan: even now, however, merely a handful of critics are prepared to consider the films in anything other than sub-Japanese terms, and one doubts whether the impetus provided by Hu’s films (which are not typical of the mainstream) is strong enough to catapult other names to equal prominence.

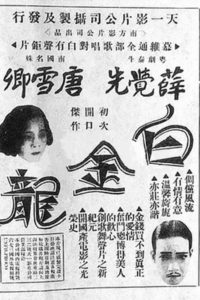

The success story of Hong Kong cinema is essentially the story of one family, Shao 邵 [Shaw], owner of a Shanghai theatre and music-hall which staged plays and silent films during the early 1920s. Shanghai at that time was the glamour and entertainment capital of mainland China, and when the family began to amass some capital two of the six sons of father Shao moved south to try their luck in Singapore – Shao Yifu 邵逸夫 [Run Run Shaw] first, followed two years later by [elder] brother Shao Renmei 邵仁枚 [Runme Shaw]. Their prime objective was distribution and property rather than production, and by the late  1920s they had built up an organisation which weathered the Depression of 1929 and went on to be the first to anticipate the success of talking pictures, en route producing the first Cantonese talkie The White Golden Dragon 白金龙 in 1932 (see poster, left). The Japanese invasion of East Asia dealt a heavy blow to the Shao empire, although the brothers are reputed to have saved a considerable portion of their wealth by the simple expedient of burying it in the ground and digging it up years later when the coast was clear. Whatever the truth, the 1950s saw the pair prosperous again with their cinema chain and property interests bigger than ever before, and in 1958 Shao Yifu again instigated another decisive move – to Hong Kong, where he found a vigorous but extremely localised film industry, churning out hundreds of b&w melodramas and comedies a year in the local dialect of Cantonese. (Written Chinese is [virtually] the same everywhere; only its pronunciation differs from region to region – Mandarin, from the Beijing region, being the “standard” pronunciation, and Cantonese, from around Hong Kong and Guangdong [Canton], being the most popular “variant”; the two pronunciations sound completely different, and educated Chinese will generally learn Mandarin as an alternative to their own dialect so as to be able to speak to non-locals.) Shao Yifu sized up the situation and decided to widen the industry’s horizons: his films would all be dubbed into the more common currency of Mandarin, with simultaneous written Chinese and English subtitles; he would use the mass of talent which had moved to Hong Kong and Taiwan when the Communists had taken over mainland China in the late 1940s; and he would film familiar historical subjects on a grand scale and in colour.

1920s they had built up an organisation which weathered the Depression of 1929 and went on to be the first to anticipate the success of talking pictures, en route producing the first Cantonese talkie The White Golden Dragon 白金龙 in 1932 (see poster, left). The Japanese invasion of East Asia dealt a heavy blow to the Shao empire, although the brothers are reputed to have saved a considerable portion of their wealth by the simple expedient of burying it in the ground and digging it up years later when the coast was clear. Whatever the truth, the 1950s saw the pair prosperous again with their cinema chain and property interests bigger than ever before, and in 1958 Shao Yifu again instigated another decisive move – to Hong Kong, where he found a vigorous but extremely localised film industry, churning out hundreds of b&w melodramas and comedies a year in the local dialect of Cantonese. (Written Chinese is [virtually] the same everywhere; only its pronunciation differs from region to region – Mandarin, from the Beijing region, being the “standard” pronunciation, and Cantonese, from around Hong Kong and Guangdong [Canton], being the most popular “variant”; the two pronunciations sound completely different, and educated Chinese will generally learn Mandarin as an alternative to their own dialect so as to be able to speak to non-locals.) Shao Yifu sized up the situation and decided to widen the industry’s horizons: his films would all be dubbed into the more common currency of Mandarin, with simultaneous written Chinese and English subtitles; he would use the mass of talent which had moved to Hong Kong and Taiwan when the Communists had taken over mainland China in the late 1940s; and he would film familiar historical subjects on a grand scale and in colour.

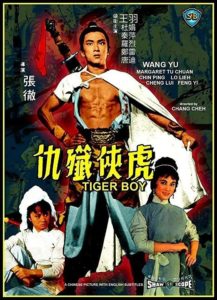

By the early 1960s Shao Yifu’s policy had paid off and the now vast studio complex atop a hill in Kowloon had already taken shape. With Shao Yifu masterminding production in Hong Kong and Shao Renmei handling distribution throughout East Asia in Singapore, the  Shaw Brothers formula was established. During the first half of the 1960s the craze became musicals, and Shaw Brothers responded with product to feed the public’s appetite. In 1964 Shao Yifu, noticing the success of many Japanese swordplay pictures, experimented (in b&w) with a Chinese variety: entitled Tiger Boy 虎侠歼仇 (1966), and starring a young contract actor [from Taiwan] called Wang Yu 王羽 and directed by [Mainland-born] ex-scriptwriter Zhang Che 张彻, it was to signal the trend for the next 10 years, a fact also confirmed by the success of Come Drink with Me 大醉侠 (1966, dir. Hu Jinquan) the same year. Hu then left Shaw Brothers to make the phenomenally successful Dragon Inn 龙门客栈 (1967), while Zhang stayed to become the studio’s number one director in the genre, bringing to prominence a whole new generation of actors and actresses, most of whom are now in the superstar league, to replace the older generation which had seen Shaw Brothers through its first years in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Shaw Brothers formula was established. During the first half of the 1960s the craze became musicals, and Shaw Brothers responded with product to feed the public’s appetite. In 1964 Shao Yifu, noticing the success of many Japanese swordplay pictures, experimented (in b&w) with a Chinese variety: entitled Tiger Boy 虎侠歼仇 (1966), and starring a young contract actor [from Taiwan] called Wang Yu 王羽 and directed by [Mainland-born] ex-scriptwriter Zhang Che 张彻, it was to signal the trend for the next 10 years, a fact also confirmed by the success of Come Drink with Me 大醉侠 (1966, dir. Hu Jinquan) the same year. Hu then left Shaw Brothers to make the phenomenally successful Dragon Inn 龙门客栈 (1967), while Zhang stayed to become the studio’s number one director in the genre, bringing to prominence a whole new generation of actors and actresses, most of whom are now in the superstar league, to replace the older generation which had seen Shaw Brothers through its first years in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

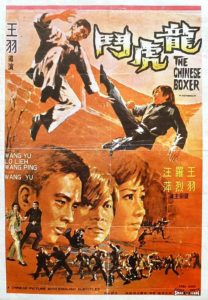

The next change of direction, or rather new slant on a waning formula, came in the late 1960s: a thoroughly Chinese equivalent of the martial-arts film, based on the unarmed techniques developed in such secret societies and monasteries as Shaolin during the Middle Ages. It was Wang Yu again who paved the way, both directing and starring in The Chinese Boxer 龙虎斗 (1970), and the cycle which the West was to dub “kung-fu” was born. At the same time, however, Shaw Brothers was dealt a body-blow which was to change the whole face of the Hong Kong industry: Zou Wenhuai 邹文怀 [Raymond Chow], Hong Kong-born and Shanghai-educated production manager who had joined the organisation in late 1958, left the company and started his own production unit, Golden Harvest, in May 1970. He was to be joined later by other Shaw Brothers personnel, including Wang.

The next change of direction, or rather new slant on a waning formula, came in the late 1960s: a thoroughly Chinese equivalent of the martial-arts film, based on the unarmed techniques developed in such secret societies and monasteries as Shaolin during the Middle Ages. It was Wang Yu again who paved the way, both directing and starring in The Chinese Boxer 龙虎斗 (1970), and the cycle which the West was to dub “kung-fu” was born. At the same time, however, Shaw Brothers was dealt a body-blow which was to change the whole face of the Hong Kong industry: Zou Wenhuai 邹文怀 [Raymond Chow], Hong Kong-born and Shanghai-educated production manager who had joined the organisation in late 1958, left the company and started his own production unit, Golden Harvest, in May 1970. He was to be joined later by other Shaw Brothers personnel, including Wang.

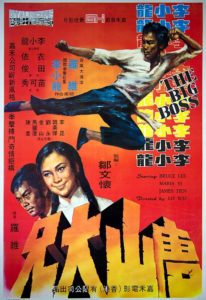

Zou, after 11½ years of working alongside Shao Yifu, had plenty of experience; all he lacked was sufficient money to realise his vision of a wider market for Chinese films, since the West was still unaware of this thriving corner of the film world (despite the fact that the Japanese industry had always enjoyed a cult following outside East Asia – something which rightly galls Hong Kong film-makers). During 1970 Golden Harvest produced a number of  pictures, none of them runaway successes; then in 1971 Zou, via a telephone call to Los Angeles, invited Li Xiaolong, an Overseas Chinese actor waiting for his big break to come in Hollywood, to star in a film called The Big Boss 唐山大兄 (1971). Li accepted Zou’s terms – which represented something of a gamble at that stage of Golden Harvest’s history – came to Hong Kong, re-worked the script, and made the film in two months in Bangkok that same year. The job done, Li returned to Los Angeles to appear in two more episodes of the TV series Longstreet (he had already done the pilot before leaving for Hong Kong), convinced that his reputation would be made there rather than in his spiritual homeland. [Though US-born, Li was raised in Hong Kong, where he was a child actor in many films; but in his late teens he was sent back to the US to further his education.] In East Asia The Big Boss caused a sensation at the box office [in late 1971, taking HK$3.2 million in Hong Kong and becoming the year’s no. 1]; but still Hollywood took no notice. Li, therefore, returned to Hong Kong to shoot Fist of Fury 精武门 (1972), the film which confirmed his superstar status in that part of the world and which provided his first introduction to Western audiences. Golden Harvest was by now beginning to challenge the mighty Shaw Brothers, and Zou had a hot property on his hands; unable to equal any of the mighty offers being made to Li, he came to an agreement to co-produce Li’s next film, The Way of the Dragon 猛龙过江 (1972), on a 50/50 basis with the star’s own company, Concord Films 协和. Li also directed.

pictures, none of them runaway successes; then in 1971 Zou, via a telephone call to Los Angeles, invited Li Xiaolong, an Overseas Chinese actor waiting for his big break to come in Hollywood, to star in a film called The Big Boss 唐山大兄 (1971). Li accepted Zou’s terms – which represented something of a gamble at that stage of Golden Harvest’s history – came to Hong Kong, re-worked the script, and made the film in two months in Bangkok that same year. The job done, Li returned to Los Angeles to appear in two more episodes of the TV series Longstreet (he had already done the pilot before leaving for Hong Kong), convinced that his reputation would be made there rather than in his spiritual homeland. [Though US-born, Li was raised in Hong Kong, where he was a child actor in many films; but in his late teens he was sent back to the US to further his education.] In East Asia The Big Boss caused a sensation at the box office [in late 1971, taking HK$3.2 million in Hong Kong and becoming the year’s no. 1]; but still Hollywood took no notice. Li, therefore, returned to Hong Kong to shoot Fist of Fury 精武门 (1972), the film which confirmed his superstar status in that part of the world and which provided his first introduction to Western audiences. Golden Harvest was by now beginning to challenge the mighty Shaw Brothers, and Zou had a hot property on his hands; unable to equal any of the mighty offers being made to Li, he came to an agreement to co-produce Li’s next film, The Way of the Dragon 猛龙过江 (1972), on a 50/50 basis with the star’s own company, Concord Films 协和. Li also directed.

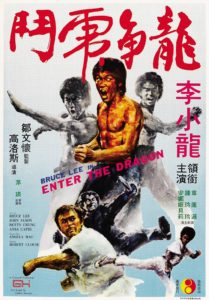

By then even Hollywood was interested. The success of the TV series Kung Fu, starring David Carradine (derived from an idea in which Li had desperately wanted to star in 1971), had proved there was a market for the fad in the US, and Warner Brothers, the company which had kept Li dangling a few years earlier, now found itself bidding for his services in Enter the Dragon 龙争虎斗 (1973), a US/Hong Kong co-production nominally directed by Robert Clouse. That over, Li, between working on the dubbing of the film, [returned to work on a film he had started shooting before Enter the Dragon, called] The Game of Death 死亡游戏. It remains uncompleted to this day [1977], despite attempts by Golden Harvest to make something of the surviving footage using contract actor Tian Jun 田俊 [James Tien]. [In 1978 a version was released under the title Game of Death 死亡游戏, patched together by Clouse with a new plot concocted by him and Zou, and using doubles for Li, including South Korean martial artist Gim Tae-jeong 김태정 | 金泰靖 and Hong Kong stuntman Yuan Biao 元彪.]

By then even Hollywood was interested. The success of the TV series Kung Fu, starring David Carradine (derived from an idea in which Li had desperately wanted to star in 1971), had proved there was a market for the fad in the US, and Warner Brothers, the company which had kept Li dangling a few years earlier, now found itself bidding for his services in Enter the Dragon 龙争虎斗 (1973), a US/Hong Kong co-production nominally directed by Robert Clouse. That over, Li, between working on the dubbing of the film, [returned to work on a film he had started shooting before Enter the Dragon, called] The Game of Death 死亡游戏. It remains uncompleted to this day [1977], despite attempts by Golden Harvest to make something of the surviving footage using contract actor Tian Jun 田俊 [James Tien]. [In 1978 a version was released under the title Game of Death 死亡游戏, patched together by Clouse with a new plot concocted by him and Zou, and using doubles for Li, including South Korean martial artist Gim Tae-jeong 김태정 | 金泰靖 and Hong Kong stuntman Yuan Biao 元彪.]

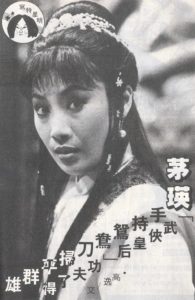

Li’s sudden death in Jul 1973 stunned the whole of East Asia; elsewhere the world was just beginning to catch up on events of the past decade, and companies, from the smallest independents to Shaw Brothers and Golden Harvest, ransacked their archives for saleable product to cash in on the sudden worldwide popularity of Hong Kong cinema. It is difficult to say how things would have turned out if Li were still alive. At the time of his death there were rumours that he was thinking of joining Shaw Brothers (which had made him a risible offer way back in the 1960s when he was unknown); certainly Hong Kong cinema would still have been on the map now [1977], rather than in the indecisive position it currently holds. The simple fact is that, despite producing several stars of international fame (Jiang Dawei 姜大卫 [David Chiang], Mao Ying 茅瑛 [Angela Mao], Luo Lie 罗烈, Wang Yu 王羽 – the first and last of whom have made English-language co-productions), Hong Kong has no one who has attracted mass attention in quite the same way as Li. This should not really be a hurdle to international acceptance (Japan’s Mifune Toshiro 三船敏郎 has never enjoyed Li-like status), but the film world does not tolerate voids.

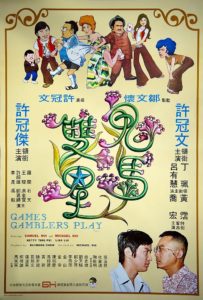

In 1975 the Hong Kong industry suffered a temporary recession, as much attributable to a lack of new directions as to financial causes. The martial-arts boom had long since petered out by then (if Li had not arrived it would have died even sooner), and producers tried every more fantastic variant in an effort to assess public taste. Golden Harvest’s production (59 films in its first five years) has now [1977] been cut back to a token number, and the  company is more interested in distribution, in line with Cathay, the large Singapore-based distributor which handles GH product. If anything, the past four years have seen a resurgence of the Cantonese film: in 1973 Shaw Brothers experimented with Cantonese soundtracks in Hong Kong, and the next year Golden Harvest enjoyed a huge success with Games Gamblers Play 鬼马双星, a satire directed by ex-Shaw Brothers actor Xu Guanwen 许冠文 [Michael Hui] and starring him and his [younger] pop-singer brother Xu Guanjie 许冠杰 [Samuel Hui]. The team’s subsequent efforts, The Last Message 天才与白痴 (1975) and The Private Eyes 半斤八两 (1976), went on to become the biggest-grossing local films of their years, the latter taking HK$8.5 million in its first run alone.

company is more interested in distribution, in line with Cathay, the large Singapore-based distributor which handles GH product. If anything, the past four years have seen a resurgence of the Cantonese film: in 1973 Shaw Brothers experimented with Cantonese soundtracks in Hong Kong, and the next year Golden Harvest enjoyed a huge success with Games Gamblers Play 鬼马双星, a satire directed by ex-Shaw Brothers actor Xu Guanwen 许冠文 [Michael Hui] and starring him and his [younger] pop-singer brother Xu Guanjie 许冠杰 [Samuel Hui]. The team’s subsequent efforts, The Last Message 天才与白痴 (1975) and The Private Eyes 半斤八两 (1976), went on to become the biggest-grossing local films of their years, the latter taking HK$8.5 million in its first run alone.

What are the general characteristics of this energetic film industry, and how does one set about fixing it in any kind of perspective? The general non-Chinese filmgoer, faced with an onslaught of unfamiliar names, faces, film titles and historical settings, is quite rightly confused, even though only a tiny proportion of Hong Kong/Taiwan production (245 films in 1973/74; 182 in 1974/65; 142 in 1975/76) ever reaches foreign shores. For the researcher the language barrier is considerable: there is plenty of information available (six regular monthlies wholly devoted to film, plus many others) but it is mostly in Chinese. Names are often difficult to distinguish, especially when printed in garbled transliterations, although many personalities adopt English Christian names to facilitate identification abroad: thus Mao Ying 茅瑛 becomes Angela Mao, Li Xiaolong 李小龙 Bruce Lee, Jiang Dawei 姜大卫 David Chiang, Miao Kexiu 苗可秀 Nora Miao, Hu Jinquan 胡金铨 King Hu, Deng Guangrong 邓光荣 Alan Tang. As an extra wrinkle on the problem, even their Chinese names are frequently stage-names, along Hollywood lines: thus actor/producer Patrick Tse is known to Chinese audiences as Xie Xian 谢贤 but in real life as Xie Jiayu 谢家钰, and it is the name Li Zhenfan 李振藩 which appears on Li Xiaolong’s gravestone.

If the names are not enough trouble, the film titles present an even greater problem. Most films are produced and released with with an official English title as well as the Chinese one (though the former frequently has no connection in meaning with the latter, and, apart  from changes during production, is sometimes different on the actual print from what appears on advertising and stills), but this is more often than not changed if a picture is sold abroad. The Big Boss 唐山大兄 (whose Chinese title means “Chinese Big Brother”) was released in the US as Fists of Fury; Fist of Fury 精武门 (literally, “Jingwu School”) became in the US The Chinese Connection, which happened to be the UK release title of Zhang Che’s Duel of Fists 拳击 (1971; literally, “Fist Attack”). At its most extreme the problem can become: The Invincible Boxer 天下第一拳 (literally, “The World’s Number One Boxer”), known in the UK [and Hong Kong] as King Boxer and in the US as Five Fingers of Death, the latter also being the UK title of Zhang Che’s Shaolin Martial Arts 洪拳与咏春 (1974)!

from changes during production, is sometimes different on the actual print from what appears on advertising and stills), but this is more often than not changed if a picture is sold abroad. The Big Boss 唐山大兄 (whose Chinese title means “Chinese Big Brother”) was released in the US as Fists of Fury; Fist of Fury 精武门 (literally, “Jingwu School”) became in the US The Chinese Connection, which happened to be the UK release title of Zhang Che’s Duel of Fists 拳击 (1971; literally, “Fist Attack”). At its most extreme the problem can become: The Invincible Boxer 天下第一拳 (literally, “The World’s Number One Boxer”), known in the UK [and Hong Kong] as King Boxer and in the US as Five Fingers of Death, the latter also being the UK title of Zhang Che’s Shaolin Martial Arts 洪拳与咏春 (1974)!

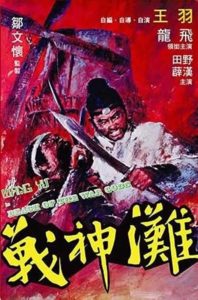

There remains, also, a final hurdle in the films themselves. Most non-Chinese have become acquainted with them in versions which bear only token resemblance to the originals – a problem confronting the enthusiast of any foreign-language cinema, but exacerbated here. Appalling Anglo-American dubbing, miserable colour duping, illogical cutting by local  distributors, plus censors’ trims, and often a music track re-dubbed in Europe – these combined have produced films which bear scant relation to the originals and nurture the popular suspicion that Hong Kong cinema lacks any sort of subtlety or technical polish. For example, the UK print of Wang Yu’s masterly Beach of the War Gods 战神滩 (1973), cut by almost a quarter-of-an-hour and featuring dark, milky colours and an array of baritone voices, gives no hint of the original’s bright, clear-cut colour photography and far less portentous range of voices. Some of this butchery is almost a distorted parody of the Hong Kong industry’s own code of practice: even the original Chinese prints do not feature the actors’ real voices (many do not speak Mandarin, and all films are post-synched by professional Mandarin dubbers) and the music tracks are often a compilation of uncredited excerpts from John Barry to Ennio Morricone, but at least the originals show a measure of appropriateness and genuine feel for dramatic form. Hong Kong censorship can also be seen at work in moments of extreme violence, but is not half so sensitive as, for instance, the British censor, who fails to see that the fantastic effects are part-and-parcel of the flamboyant whole and not half as damaging as the morbidly realistic violence allowed to slip through in American product.

distributors, plus censors’ trims, and often a music track re-dubbed in Europe – these combined have produced films which bear scant relation to the originals and nurture the popular suspicion that Hong Kong cinema lacks any sort of subtlety or technical polish. For example, the UK print of Wang Yu’s masterly Beach of the War Gods 战神滩 (1973), cut by almost a quarter-of-an-hour and featuring dark, milky colours and an array of baritone voices, gives no hint of the original’s bright, clear-cut colour photography and far less portentous range of voices. Some of this butchery is almost a distorted parody of the Hong Kong industry’s own code of practice: even the original Chinese prints do not feature the actors’ real voices (many do not speak Mandarin, and all films are post-synched by professional Mandarin dubbers) and the music tracks are often a compilation of uncredited excerpts from John Barry to Ennio Morricone, but at least the originals show a measure of appropriateness and genuine feel for dramatic form. Hong Kong censorship can also be seen at work in moments of extreme violence, but is not half so sensitive as, for instance, the British censor, who fails to see that the fantastic effects are part-and-parcel of the flamboyant whole and not half as damaging as the morbidly realistic violence allowed to slip through in American product.

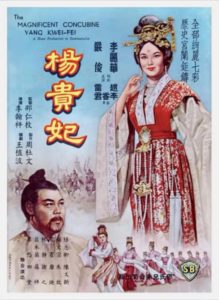

Thanks to the ability (equalled only by Indians) of Chinese abroad to set up self-contained societies, it is not difficult for interested parties to experience the original versions of films; the UK alone has a late-night circuit encompassing London, Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Newcastle, Leeds, Bristol and Southampton. And the observant student will have noticed that signs of Asian activity have trickled through over the years: in 1962 The Magnificent Concubine 杨贵妃 (dir. Li Hanxiang 李翰祥), one of Shaw Brothers’ earliest successes and with a foreword by none other than [Sinophile US author] Pearl S. Buck, [co-won a technical award for photography] at Cannes; [two other Li films, The Enchanting Shadow 倩女幽魂, 1960, and

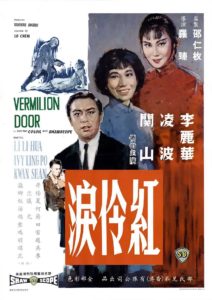

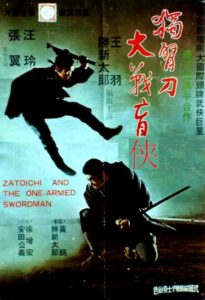

Thanks to the ability (equalled only by Indians) of Chinese abroad to set up self-contained societies, it is not difficult for interested parties to experience the original versions of films; the UK alone has a late-night circuit encompassing London, Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Newcastle, Leeds, Bristol and Southampton. And the observant student will have noticed that signs of Asian activity have trickled through over the years: in 1962 The Magnificent Concubine 杨贵妃 (dir. Li Hanxiang 李翰祥), one of Shaw Brothers’ earliest successes and with a foreword by none other than [Sinophile US author] Pearl S. Buck, [co-won a technical award for photography] at Cannes; [two other Li films, The Enchanting Shadow 倩女幽魂, 1960, and  Empress Wu 武则天, 1963, also competed at Cannes in 1960 and 1963, all representing “China”;] another Shaw Brothers film, Vermilion Door 红伶泪 (1964, dir. Luo Zhen 罗臻), starring Ling Bo 凌波, Li Lihua 李丽华 and Guan Shan 关山, was the Hong Kong entry in the Commonwealth Film Festival held at [London’s] National Film Theatre in Sep 1965; films from Asia were shown at a special festival in Frankfurt in the spring of the same year; in 1970 the Edinburgh Film Festival even screened a South Korean melodrama, and by 1973 [London’s] enterprising New Cinema Club run by Derek Hill was showing programmes of Hong Kong trailers and [the Japan/Hong Kong co-production] Zatoichi and the One-Armed Swordsman 独臂刀大战盲侠 (1971, co-dirs. Xu Zenghong 徐增宏, Yasuda Kimiyoshi 安田公义), the latter never publicly screened even in its dubbed version. And if

Empress Wu 武则天, 1963, also competed at Cannes in 1960 and 1963, all representing “China”;] another Shaw Brothers film, Vermilion Door 红伶泪 (1964, dir. Luo Zhen 罗臻), starring Ling Bo 凌波, Li Lihua 李丽华 and Guan Shan 关山, was the Hong Kong entry in the Commonwealth Film Festival held at [London’s] National Film Theatre in Sep 1965; films from Asia were shown at a special festival in Frankfurt in the spring of the same year; in 1970 the Edinburgh Film Festival even screened a South Korean melodrama, and by 1973 [London’s] enterprising New Cinema Club run by Derek Hill was showing programmes of Hong Kong trailers and [the Japan/Hong Kong co-production] Zatoichi and the One-Armed Swordsman 独臂刀大战盲侠 (1971, co-dirs. Xu Zenghong 徐增宏, Yasuda Kimiyoshi 安田公义), the latter never publicly screened even in its dubbed version. And if  the word “kung-fu” seemed new in 1973, it is worth remembering that a certain Malaysian company had run an advertisement in the Odeon [cinema] circuit’s Showtime magazine a full seven years earlier, exhorting patrons: “Don’t Be Bullied! You Too Can Become a Fearless Exponent of Chinese Kung-Fu Karato [sic]…the Authentic Chinese Self-Defence Art That Disables Instantaneously on Contact…”

the word “kung-fu” seemed new in 1973, it is worth remembering that a certain Malaysian company had run an advertisement in the Odeon [cinema] circuit’s Showtime magazine a full seven years earlier, exhorting patrons: “Don’t Be Bullied! You Too Can Become a Fearless Exponent of Chinese Kung-Fu Karato [sic]…the Authentic Chinese Self-Defence Art That Disables Instantaneously on Contact…”

Stylistically – and from hereon I am concerned with the whole spectrum of Hong Kong/Taiwan cinema, not just the martial-arts films – the films draw on a variety of sources. The Italian industry is Europe’s closest equivalent, and Hong Kong cinema, with its inexhaustible energy, optimism, extrovert craftsmanship, and powers of adaptability and self-renewal, is tailor-made to appeal to anyone who mourns the passing of Italy’s peplum genre and the era of “spaghetti westerns” which followed it. The Chinese sword-hero unites the resonant [Sergio] Leone-spawned Italian gunfighter with the lone Japanese samurai, and comes up with its own unique invention. Since the mid-1960s almost all films have been shot in colour and scope (the latter process not using Panavision equipment, so some distortion results, but the demands of TV have not compromised directors into using widescreen ratios instead), and film-makers have made the fullest use of their opportunities, tracking, zooming and changing set-ups with a frequency which rids the scope screen of the sense of cumbersomeness which afflicted many American productions. In general, Hong Kong cinema disdains the traditional master-shot in favour of fresh camera set-ups for every cut; partly this reflects the rapid shooting schedules demanded by the small budgets but it equally reflects a tendency to identify the camera – and thus the audience – totally with the storyline – a thorough “realisation” in cinematic terms rather than working the story to fit existing shooting manners.

In the martial-arts films most of the time is taken up with preparing and shooting the elaborate fight scenes, with minimum rehearsal and number of takes for dialogue passages. The resultant brio carries over, however, into other genres, notably the stream of glossy modern melodramas mostly shot in Taiwan (none of which, sadly, have ever been shown publicly in the UK), which show similar approaches to their subjects and often feature songs or song-montages in place of fight sequences. Between the two stands the horror film genre, which has produced some of Hong Kong cinema’s finest works: frequent use is made of China’s vast literary legacy of ghost tales, and their realisation exploits to the full the possibilities of uniting the fantastique elements of the martial-arts genre with a taste for true horror which shames [UK specialist] Hammer Films into insignificance.

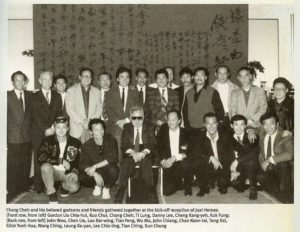

In the brief scope of this article it is possible only to sketch the personalities and themes at work, and one must perforce pass over the wide range of other genre: gangster films, Cantonese opera, comedies, period romances, thrillers, war films – in fact, as wide a range, if not wider (with the possibilities offered by the Asian equivalents), than Western cinema. The Hong Kong industry is star-oriented and devoted to (in the words of Shao Yifu) “giving  the public what it wants”, though this does not preclude at all, just as it did not preclude Hollywood film-makers in the studio days, a degree of personal expression and individual style. Plots may be formulary, and acting styles disconcertingly histrionic for Western tastes (particularly the much-used “surprised reaction” shot), but one must accept these as normal characteristics of Hong Kong cinema, rather than try to force the films into Western moulds. Even working within the rigid Shaw Brothers set-up, directors have carved their own personal styles, and (in, for instance, the case of Li Hanxiang) spells outside the studio system have not necessarily been beneficial. Zhang Che, Shaw Brothers’ foremost martial-arts director, has since the early 1970s set up his own company and worked with a regular repertory team of actors (see picture, above); but he is still linked with the studio in all but name. Shao Yifu runs the Hong Kong set-up with the precision and ruthlessness of a trained accountant: every year a certain number of trainee actors are accepted, put in an iron-clad contract on a token income, and housed, trained and used by the studio to the best of their ability.

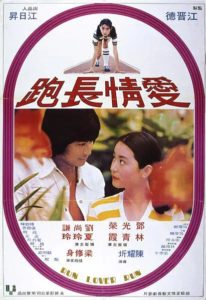

the public what it wants”, though this does not preclude at all, just as it did not preclude Hollywood film-makers in the studio days, a degree of personal expression and individual style. Plots may be formulary, and acting styles disconcertingly histrionic for Western tastes (particularly the much-used “surprised reaction” shot), but one must accept these as normal characteristics of Hong Kong cinema, rather than try to force the films into Western moulds. Even working within the rigid Shaw Brothers set-up, directors have carved their own personal styles, and (in, for instance, the case of Li Hanxiang) spells outside the studio system have not necessarily been beneficial. Zhang Che, Shaw Brothers’ foremost martial-arts director, has since the early 1970s set up his own company and worked with a regular repertory team of actors (see picture, above); but he is still linked with the studio in all but name. Shao Yifu runs the Hong Kong set-up with the precision and ruthlessness of a trained accountant: every year a certain number of trainee actors are accepted, put in an iron-clad contract on a token income, and housed, trained and used by the studio to the best of their ability.  Aside from Golden Harvest, which is run on substantially more modest lines, there is an impressive line-up of other production companies, which dip into the freelance acting pool for a star or two to headline a production. First 第一 and Goldig 协利 are the most enterprising, with production running at between six to a dozen pictures a year; Xie Xian directs and produces his own films, generally glossy Taiwan melodramas with his (now ex-) wife Zhen Zhen 甄珍 [one of which, Fantasies behind the Pearly Curtain 一帘幽梦, 1975, dir. Bai Jingrui 白景瑞, provides the title of this article, see left]; Guo Nanhong 郭南宏, an independent producer/director, has recently had a string of successes revolving around a blatantly derivative re-working of the Shaolin cycle; and Great Wall 长城, unofficially linked with mainland China, produces product halfway between the politically-oriented films of Beijing and Shanghai, and the success-oriented mainstream of Hong Kong.

Aside from Golden Harvest, which is run on substantially more modest lines, there is an impressive line-up of other production companies, which dip into the freelance acting pool for a star or two to headline a production. First 第一 and Goldig 协利 are the most enterprising, with production running at between six to a dozen pictures a year; Xie Xian directs and produces his own films, generally glossy Taiwan melodramas with his (now ex-) wife Zhen Zhen 甄珍 [one of which, Fantasies behind the Pearly Curtain 一帘幽梦, 1975, dir. Bai Jingrui 白景瑞, provides the title of this article, see left]; Guo Nanhong 郭南宏, an independent producer/director, has recently had a string of successes revolving around a blatantly derivative re-working of the Shaolin cycle; and Great Wall 长城, unofficially linked with mainland China, produces product halfway between the politically-oriented films of Beijing and Shanghai, and the success-oriented mainstream of Hong Kong.

How does one reach any point of reference in the array of unfamiliar faces? In fact, there are quite clear divisions, and once one has become used to recognising individual features, the personalities also emerge. Of actors who are chiefly identified with martial-arts films, the following are the most notable: Li Xiaolong 李小龙, of course, whose brand of panther-like intensity (like a coiled spring) was a physical expression of the intense Chinese

How does one reach any point of reference in the array of unfamiliar faces? In fact, there are quite clear divisions, and once one has become used to recognising individual features, the personalities also emerge. Of actors who are chiefly identified with martial-arts films, the following are the most notable: Li Xiaolong 李小龙, of course, whose brand of panther-like intensity (like a coiled spring) was a physical expression of the intense Chinese  nationalism which runs through his films; Wang Yu 王羽, ex-Shaw Brothers trainee actor of uninspiring physique but steel-cold gaze, whose characters are marked by an obsessional interest in self-mutilation and physical constraint; Jiang Dawei 姜大卫, ex-stuntman (who worked on The Sand Pebbles, 1966) turned Shaw Brothers contract artist, of diminutive boyish appearance but great agility, often teamed with the more impressive Di Long 狄龙, who specialises in lone charismatic heroes dispensing ruthless personal justice; Fu Sheng 傅声, like the previous two a Zhang Che 张彻 alumnus, who is used as a lightweight jokey balance which accords well with his thoroughly pop-idol image; and the more stolid Chen Guantai 陈观泰, Luo Lie 罗烈, Yue Hua 岳华, and (especially good at smooth villainy) Gu Feng 谷峰. All these

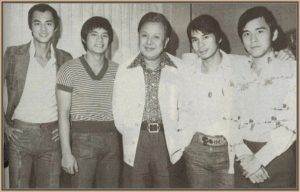

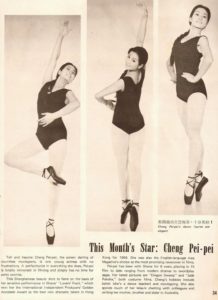

nationalism which runs through his films; Wang Yu 王羽, ex-Shaw Brothers trainee actor of uninspiring physique but steel-cold gaze, whose characters are marked by an obsessional interest in self-mutilation and physical constraint; Jiang Dawei 姜大卫, ex-stuntman (who worked on The Sand Pebbles, 1966) turned Shaw Brothers contract artist, of diminutive boyish appearance but great agility, often teamed with the more impressive Di Long 狄龙, who specialises in lone charismatic heroes dispensing ruthless personal justice; Fu Sheng 傅声, like the previous two a Zhang Che 张彻 alumnus, who is used as a lightweight jokey balance which accords well with his thoroughly pop-idol image; and the more stolid Chen Guantai 陈观泰, Luo Lie 罗烈, Yue Hua 岳华, and (especially good at smooth villainy) Gu Feng 谷峰. All these  actors often appear in modern gangster or crime dramas, in similarly physical roles (see top, left to right, Di Long, Fu Sheng, director Zhang Che, Chen Guantai, Jiang Dawei). On the distaff side, Hong Kong boasts an impressive line-up of martial-arts actresses, almost all of whom originally trained as dancers: Mao Ying 茅瑛, short, spunky Taiwan ex-ballet star (see centre left), specialising in restrained, morally ascetic characters (and generally under the measured direction of Huang Feng 黄枫); Zheng Peipei 郑佩佩, a tall, extremely supple dancer (now retired from films and running a dance school in Los Angeles) of impressive stature and phenomenal toughness (see bottom left); Shi Si 施思, a Shaw Brothers actress of more conventional looks but abrasive personality; Xu Feng 徐枫, a highly charismatic Taiwan actress of no special agility but suggesting a remote, misty-eyed sexuality behind the ruthless exterior; Jia Ling 嘉凌, a somewhat pert actress of noticeable flexibility, who also sports a nice line in comedy; and the fiery, tomboyish Shangguan Lingfeng 上官灵凤.

actors often appear in modern gangster or crime dramas, in similarly physical roles (see top, left to right, Di Long, Fu Sheng, director Zhang Che, Chen Guantai, Jiang Dawei). On the distaff side, Hong Kong boasts an impressive line-up of martial-arts actresses, almost all of whom originally trained as dancers: Mao Ying 茅瑛, short, spunky Taiwan ex-ballet star (see centre left), specialising in restrained, morally ascetic characters (and generally under the measured direction of Huang Feng 黄枫); Zheng Peipei 郑佩佩, a tall, extremely supple dancer (now retired from films and running a dance school in Los Angeles) of impressive stature and phenomenal toughness (see bottom left); Shi Si 施思, a Shaw Brothers actress of more conventional looks but abrasive personality; Xu Feng 徐枫, a highly charismatic Taiwan actress of no special agility but suggesting a remote, misty-eyed sexuality behind the ruthless exterior; Jia Ling 嘉凌, a somewhat pert actress of noticeable flexibility, who also sports a nice line in comedy; and the fiery, tomboyish Shangguan Lingfeng 上官灵凤.

On the other side of the coin are those personalities who mostly avoid historical or fighting heroics: Zhen Zhen 甄珍, long-reigning Mandarin melodrama queen (now in her 30s) of impressive Audrey Hepburn-like range and character, from gamine to high-society lady; Deng Guangrong 邓光荣 [Alan Tang], frequently her film partner, with more than a passing parallel to Alain Delon; Lin Qingxia 林青霞 [Brigitte Lin], slim, “blue-jeaned” ex-teenage challenge to Zhen Zhen’s position, who in four years has risen from obscurity to no. 2 attraction and shown an affecting depth of characterisation; Qin Xianglin 秦祥林, often teamed with her (see left), who displays considerably more range than the wooden Deng and who has a George Segal-like gift for light comedy which is too little used. One cannot possibly mention even a quarter of the remaining major personalities, but some will doubtless be familiar to readers: Miao Kexiu 苗可秀 [Nora

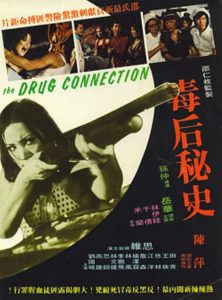

On the other side of the coin are those personalities who mostly avoid historical or fighting heroics: Zhen Zhen 甄珍, long-reigning Mandarin melodrama queen (now in her 30s) of impressive Audrey Hepburn-like range and character, from gamine to high-society lady; Deng Guangrong 邓光荣 [Alan Tang], frequently her film partner, with more than a passing parallel to Alain Delon; Lin Qingxia 林青霞 [Brigitte Lin], slim, “blue-jeaned” ex-teenage challenge to Zhen Zhen’s position, who in four years has risen from obscurity to no. 2 attraction and shown an affecting depth of characterisation; Qin Xianglin 秦祥林, often teamed with her (see left), who displays considerably more range than the wooden Deng and who has a George Segal-like gift for light comedy which is too little used. One cannot possibly mention even a quarter of the remaining major personalities, but some will doubtless be familiar to readers: Miao Kexiu 苗可秀 [Nora  Miao], who sadly was never allowed to fulfil the promise of her early Golden Harvest roles (viz. the hopeless parts in Li Xiaolong’s films); Li Jing 李菁, the toast of East Asia during the 1960s, but now having more success with her monthly agony column and as a Shaw Brothers ambassadress, than in hard film roles; Chen Ping 陈萍, Hong Kong’s own sex queen, recently diversifying into a breathtaking series of female vigilante pictures (see The Drug Connection 毒后秘史, 1976, left); Lu Yan 卢燕 [Lisa Lu], Hollywood-reared Chinese actress, who returned in triumph to make two large-scale Shaw Brothers costume pictures; Li Lihua 李丽华 and Ling Bo 凌波, both representing the older generation of actresses who date from the 1950s and early 1960s; Miao Tian 苗天, grizzled actor/producer of wide experience and erudition…

Miao], who sadly was never allowed to fulfil the promise of her early Golden Harvest roles (viz. the hopeless parts in Li Xiaolong’s films); Li Jing 李菁, the toast of East Asia during the 1960s, but now having more success with her monthly agony column and as a Shaw Brothers ambassadress, than in hard film roles; Chen Ping 陈萍, Hong Kong’s own sex queen, recently diversifying into a breathtaking series of female vigilante pictures (see The Drug Connection 毒后秘史, 1976, left); Lu Yan 卢燕 [Lisa Lu], Hollywood-reared Chinese actress, who returned in triumph to make two large-scale Shaw Brothers costume pictures; Li Lihua 李丽华 and Ling Bo 凌波, both representing the older generation of actresses who date from the 1950s and early 1960s; Miao Tian 苗天, grizzled actor/producer of wide experience and erudition…

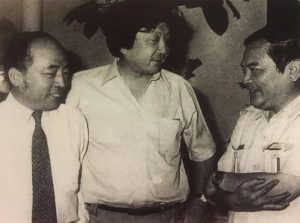

One may reasonably wonder whether the director’s name can sell a picture at all in such an atmosphere, but certain personalities (for it is essentially around personalities that the cut-throat industry is organised) do have a public following. The small but painstaking oeuvre of Hu Jinquan (right in picture, with Bai Jingrui, left, and Li Xing, centre), consciously striving after a more Western-style mise-en-scène while using thoroughly Chinese material, has so far peaked in A Touch of Zen and the fluid The Fate of Lee Khan (1973), both emphasising the intangible

One may reasonably wonder whether the director’s name can sell a picture at all in such an atmosphere, but certain personalities (for it is essentially around personalities that the cut-throat industry is organised) do have a public following. The small but painstaking oeuvre of Hu Jinquan (right in picture, with Bai Jingrui, left, and Li Xing, centre), consciously striving after a more Western-style mise-en-scène while using thoroughly Chinese material, has so far peaked in A Touch of Zen and the fluid The Fate of Lee Khan (1973), both emphasising the intangible  qualities of the martial arts. Li Hanxiang’s dazzling collection of ornate costume dramas in imperial settings – most recently, The Empress Dowager 倾国倾城 (1975) and The Last Tempest 瀛台泣血 (1976), both starring Lu Yan – and “traditional” erotic comedies (see picture left, directing Empress Dowager). Zhang Che’s systematic exploration of facets of heroism through the martial arts (50-plus films since 1964), currently floundering in an excess of technique and shortage of new

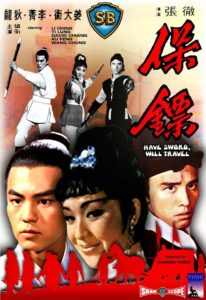

qualities of the martial arts. Li Hanxiang’s dazzling collection of ornate costume dramas in imperial settings – most recently, The Empress Dowager 倾国倾城 (1975) and The Last Tempest 瀛台泣血 (1976), both starring Lu Yan – and “traditional” erotic comedies (see picture left, directing Empress Dowager). Zhang Che’s systematic exploration of facets of heroism through the martial arts (50-plus films since 1964), currently floundering in an excess of technique and shortage of new  ideas, but (especially his Shaw Brothers work during the late 1960s like Golden Swallow 金燕子, 1968, with Wang Yu and Zheng Peipei, known in the UK as The Girl with the Thunderbolt Kick, and Have Sword, Will Travel 保镖, 1969, with Di Long and Jiang Dawei) formerly of appealing sensuousness and vigour. In the field of melodrama, [Taiwan veteran] Li Xing 李行 has re-worked old models with tact and style: the classic Execution in Autumn 秋决 (1972), a moving tale of spiritual rebirth set during the Han dynasty, The Marriage 婚姻大事 (1974), which escalates a formulary Taiwan-glossy plot through ludicrasy to ludicrasy, and the stridently anti-Japanese Land of the Undaunted 吾土吾民 (1975). The young US-trained director Chen Yaoqi 陈耀圻 [Richard Chen] is also fulfilling the promise of his early

ideas, but (especially his Shaw Brothers work during the late 1960s like Golden Swallow 金燕子, 1968, with Wang Yu and Zheng Peipei, known in the UK as The Girl with the Thunderbolt Kick, and Have Sword, Will Travel 保镖, 1969, with Di Long and Jiang Dawei) formerly of appealing sensuousness and vigour. In the field of melodrama, [Taiwan veteran] Li Xing 李行 has re-worked old models with tact and style: the classic Execution in Autumn 秋决 (1972), a moving tale of spiritual rebirth set during the Han dynasty, The Marriage 婚姻大事 (1974), which escalates a formulary Taiwan-glossy plot through ludicrasy to ludicrasy, and the stridently anti-Japanese Land of the Undaunted 吾土吾民 (1975). The young US-trained director Chen Yaoqi 陈耀圻 [Richard Chen] is also fulfilling the promise of his early  pictures; the equally delightful Run Lover Run 爱情长跑 (1975) and The Chasing Game 追球追求 (1976), both starring Lin Qingxia, question the social and sexual ethics of modern Taiwan melodramas with a [Howard] Hawksian glee. Space prevents mention of myriad other talents – Bai Jingrui 白景瑞, the temporarily eclipsed Luo Wei 罗维, Liu Jiachang 刘家昌, Song Cunshou 宋存寿, Tang Shuxuan 唐书璇, Xu Guanwen 许冠文 [Michael Hui]… the list is endless and constantly renewing itself. And if, throughout this brief introduction to Hong Kong/Taiwan cinema, I have concentrated more on facts than themes, on the hows rather than the whys, that is because ultimately the films speak for themselves, with a clarity and directness which curries to no pretensions other than entertainment and recognises no artificial division between that word and “art”.

pictures; the equally delightful Run Lover Run 爱情长跑 (1975) and The Chasing Game 追球追求 (1976), both starring Lin Qingxia, question the social and sexual ethics of modern Taiwan melodramas with a [Howard] Hawksian glee. Space prevents mention of myriad other talents – Bai Jingrui 白景瑞, the temporarily eclipsed Luo Wei 罗维, Liu Jiachang 刘家昌, Song Cunshou 宋存寿, Tang Shuxuan 唐书璇, Xu Guanwen 许冠文 [Michael Hui]… the list is endless and constantly renewing itself. And if, throughout this brief introduction to Hong Kong/Taiwan cinema, I have concentrated more on facts than themes, on the hows rather than the whys, that is because ultimately the films speak for themselves, with a clarity and directness which curries to no pretensions other than entertainment and recognises no artificial division between that word and “art”.

(Article originally published in UK annual Film Review, late 1977. Modern annotations in square brackets.)