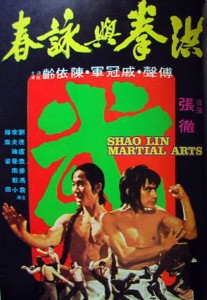

Shao Lin Martial Arts

洪拳与咏春

Hong Kong, 1974, colour, 2.35:1, 105 mins.

Director: Zhang Che 张彻.

Rating: 7/10.

Drama centred on rival martial-arts techniques shows director Zhang Che in his best and most rigorous form.

Guangzhou province, early Qing dynasty. Su (Li Yunzhong), a general in the Manchu army, brings down two fighters from the north – Ba Gang (Liang Jiaren) and Yu Bi (Wang Longwei) – to challenge fighters from the local Shaolin martial arts school, run by Lin Cantian (Lu Di), which is being used as a resistance centre against the Manchu government. Following the success of Ba Gang and Yu Bi, Lin Cantian sends two of his pupils, He Zhen’gang (Liu Jiahui) and Mai Han (Tang Yancan), to study special techniques under retired Shaolin master Ying Zhuawang (Jiang Nan) that can beat the Manchu fighters. However, the techniques are not strong enough: He Zhen’gang and Mai Han both die. Lin Cantian then sends his best pupils, Li Yao (Fu Sheng) and Chen Baorong (Qi Guanjun), for specialist training under other Shaolin masters. Meanwhile, Lin Cantian commits suicide when threatened with arrest by the Manchu. His daughter, Lin Zhenxiu (Chen Yiling), and her friend Hui (Yuan Manzi) escape and follow after Li Yao and Chen Baorong.

REVIEW

With seven films in distribution, Zhang Che 张彻 is currently the best represented Hong Kong director in this country [the UK, as of late 1975]. Suffice it to say that Shao Lin Martial Arts 洪拳与咏春 shows Zhang in his best, and at the same time most rigorous, form. Hastily made in 1974, the film has received the full [London] West End treatment from a major distributor [Columbia-Warner] – something of a rarity in these post-Li Xiaolong 李小龙 [Bruce Lee] days, when martial arts films are invariably released straight to the provinces in double bills. This one deserves special consideration, however, despite the fact that (a) it has been needlessly trimmed of some of its footage [around 15 minutes], (b) has been saddled with a [UK release] title [Five Fingers of Death] that is dangerously close to Five Fingers of Steel, the American title of King Boxer 天下第一拳 (1972), and (c) released in its dubbed rather than subtitled version. None of the preceding facts are new with regard to Chinese films; one might have hoped, however, that by now – and especially considering the excellent quality of the print used – the distributor might have had the courage to show the work in its integral form.

The original title stressed the formal aspect of the film: “Hong Boxing and Yongchun [Technique]” – a point that was retained in the Hong Kong English title of Shao Lin Martial Arts. Zhang’s fascination during the last five years with the mechanics of the martial arts rather than their results forms the persistent theme of the picture, and the elaborate scenes of training and work-outs contain sufficient development and suspense to qualify as major plot elements rather than simple appendages. A similar approach was discernible in Men from the Monastery 少林子弟 (1974, recently released here [in the UK] as The Dragon’s Teeth), but even there story took the upper hand at crucial moments. Shao Lin Martial Arts, of all Zhang’s Shaolin films, is the nearest in approach to the “pure” style of Golden Harvest’s Hap Ki Do 合气道 (1972) and the like, despite its visual indebtedness to the Shaw studios. For, despite the fact of it having been made in Zhang’s “post-Shaw” period, its studio-bound production and rich, colourful photography conjure up memories of earlier, more flamboyant pictures like The Boxer from Shantung 马永贞 (1972).

And as one might expect, that focus is ever more exclusively masculine. The machismo element of many martial arts pictures, which Li plundered but often satirised, finds its culmination in Zhang’s films. Feminine interest is generally nominal, to say the least, and in many of his recent works has been practically non-existent. His present repertory company, composed of Fu Sheng 傅声, Qi Guanjun 戚冠军, Chen Guantai 陈观泰, Jiang Dawei 姜大卫 [David Chiang], Di Long 狄龙 and Meng Fei 孟飞, plus many other regulars, combine the romantic with the narcissistic, the serious with the comical, but always in a purely masculine universe in which physical prowess represents the true end of existence. In the present work, as in others, Qi indulges most frequently in [Steve] Reeves-like displays of perspiring muscularity, with Fu typically cast as his less obsessive foil. It is a familiar combination, but carefully balanced: when both knuckle down to serious training, dedication is never less apparent in one than the other, only their approach differs.

The background of Manchu persecution of Shaolin disciples is hardly developed beyond providing a sufficient excuse to place various fighting techniques in opposition. Considerable ingenuity is spent on trying to find the right technique to combat another – a dominant motif in such films but not necessarily the most important one, as here – and with respect towards the conventions of the genre, the heroes are made to fail before they can succeed. The remainder of the film is composed of a series of disciplines for each of the fighters: Fu must first win over his teacher’s sympathies before he can begin to learn the Tiger and Stork techniques, while Qi must be brought to the edge of despair before proceeding to proper training. Zhang’s consummate editing skills [carried out by editor Guo Tinghong 郭廷鸿] make much of such lengthy sequences, and with heroic accompanying music (pounding chords in the carp-catching scenes) they attain a hymnic level. Zhang’s universe is every bit as violent and unfriendly as in such costume pictures as The Deaf and Mute Heroine 聋哑剑 (Wu Ma 午马, 1971), but on a more refined level. Obligation and honour weigh heavy on the characters, and those unfit to carry the name of their art are rigorously eliminated. Zhang is one of the few Hong Kong directors to have single-mindedly explored all alleys of approach to the martial arts film, and his own personal style, which has as many glosses as films made, can be seen at its most naked in Shao Lin Martial Arts.

CREDITS

Presented by Shaw Brothers (HK). Produced by Chang’s Film (HK).

Script: Ni Kuang, Zhang Che. Photography: Gong Muduo [Miyaki Yukio]. Editing: Guo Tinghong. Music: Chen Yongyu [Chen Xunqi/Frankie Chan]. Art direction: Fang Chao. Costumes: Li Qi. Sound: Wang Yonghua. Action: Tang Jia, Liu Jialiang.

Cast: Fu Sheng (Li Yao), Qi Guanjun (Chen Baorong), Chen Yiling (Lin Zhenxiu), Liu Jiahui (He Zhen’gang), Tang Yancan (Mai Han), Lu Di (Lin Cantian, Lin Zhenxiu’s father), Yuan Manzi (Hui, Lin Zhenxiu’s friend), Jiang Nan (Ying Zhuawang, retired Shaolin master), Feng Yi (Yan Dongtian, Shaolin master), Yuan Xiaotian (Liang Hong, Shaolin master), Liang Jiaren (Ba Gang, Manchu fighter), Wang Longwei (Yu Bi, Manchu fighter), Li Yunzhong (Su, Manchu general), Feng Ke’an (He Lian), Jiang Dao (Wu Songping), Li Zhenbiao (big master), Liu Jiarong (Luo, Shaolin master), Chen Tianlong, Zheng Wenru, Xu Xia, Lu Wei, Lu Jianming, Lin Huihuang, Ye Tianxing, Qi Yixiong, Deng Yancheng, Yin Fa, Wang Jiang, Huang Xia, Huang Shutang, Chen Guokun, Chen Dike.

Release: Hong Kong, 3 Aug 1974.

(Review section originally published in UK monthly films and filming, Feb 1976, as Five Fingers of Death. Modern annotations in square brackets.)