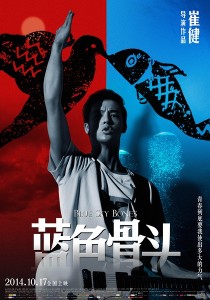

Blue Sky Bones

蓝色骨头

China, 2013, colour, 1.85, 104 mins.

Director: Cui Jian 崔健.

Rating: 8/10.

Mainland rocker Cui Jian’s first feature is a powerful lament for a lost generation.

Wuxi, Chongqing, the early 1980s. Army intelligence agent Zhong Zhenqing (Zhao Youliang) returns home to his emotionally unstable wife Shi Yanping (Ni Hongjie). A violent argument ensues, Zhong Zhenqing makes off with his young son Zhong Hua on a motorcycle, and he is accidentally wounded when a gun goes off. Twenty years later, in Beijing, Zhong Hua (Yin Fang) is a struggling songwriter who also uploads viruses with songs so he can then sell the anti-virus. He’s called back home by Auntie Zou (Xiong Ruiling) who says his father is seriously ill with advanced testicular cancer which has spread to his spine. Zhong Hua tells her he’ll find the RMB100,000 for the treatment. (In 1970, during the midst of the Cultural Revolution, Shi Yanping had arrived in Beijing from Sichuan province to enter a music and dance academy, and was fixed up with a boyfriend by the academy’s head, Zhang [Mao Amin]. The boy, also in the academy, was a dancer, Sun Hong [Tao Ye], the son of a general; but Sun Hong was more interested in his male roommate, Chen Dong (Huang Xuan), than Shi Yanping, and when Shi Yanping and Chen Dong fell for each other the three formed a close emotional triangle. Chen Dong and Shi Yanping wrote a song for Sun Hong to perform to, but when the material was deemed to be politically problematic the men were sent back home and Shi Yanping – already under scrutiny for her unhealthy interest in western pop music – was also expelled in 1972. After the Cultural Revolution she finally married Zhong Zhenqing, whom she first got to know when he worked as a driver; the marriage was more from convenience than love, and Zhong Zhenqing was often away on intelligence missions.) Meanwhile, Zhong Hua gets the money he needs for his father’s treatment by agreeing to “package” a wannabe singer, Mengmeng (Huang Huan), the girlfriend of a music promoter friend, Xu Tian (Guo Jinglin). Mengmeng seduces Zhong Hua, and he writes a song for her, The Love of Fish and Bird 鸟鱼之恋, based on his parents’ relationship. Meanwhile, Zhong Zhenqing, realising he is dying, decides to travel home to find Shi Yanping one last time. In Beijing, Zhong Hua prepares a live web show by illegally hooking into a computer dish. The song he’ll perform is Blue Sky Bones, based on Shi Yanping and Chen Dong’s banned work, The Lost Season 迷失的季节.

REVIEW

The old maxim that “you’re only as good as your last film” proves happily wrong in the case of Mainland rock legend Cui Jian 崔健, whose first feature, Blue Sky Bones 蓝色骨头, is as beautifully accomplished as his last exercise as a film-maker – the 30-minute segment, 2029, in the two-part movie Chengdu, I Love You 成都,我爱你 (2009) – was laughably inept. Set in Chongqing in the early 2000s, Bones is a challenging look at the lost generation of the Cultural Revolution through the eyes of a young songwriter who’s trying to make sense of his life in an age of the internet, music downloading and forgetfulness of the past. Where the futuristic 2029 was a chaotic jumble of ideas, Bones, despite a few weaknesses, has a strong emotional thread to carry the audience through the flashbacks to the past and the jungle of thoughts expressed by the central character in his philosophical voiceover.

Cui has modestly described his role on the film as “orchestrating the actors, the music and the script” and leaving the rest of the production work to professionals in each field. He’s chosen his team wisely, including veteran Australian cinematographer Christopher Doyle 杜可风 (who’s spent a lifetime working on movies by top Chinese directors), Mainland editor Zhou Xinxia 周新霞, and a cast including versatile young actress Ni Hongjie 倪虹洁 (My Own Swordsman 武林外传, 2011; One Night Surprise 一夜惊喜, 2013; Silent Witness 全民目击, 2013) as the boy’s rebellious mother, Huang Xuan 黄轩and Tao Ye 陶冶 as the two men in her youth, and the older Zhao Youliang 赵有亮 (the Daoist master in An End to Killing 止杀, 2012) as the boy’s father.

Cui has acknowledged Doyle as the “axis” of the team, and the latter’s cinematography is a major part of the film’s success, from the saturated reds and army greens in the Cultural Revolution sequences to his striking compositions throughout. Doyle’s photography brings atmosphere and shape to the story as it shuttlecocks between past and present – from the “young love” triangle of the 1970s between the boy’s future mother, her true love and his tortured, gay friend, to the early 2000s as the son, trying to make a career as a songwriter, finds himself sexually and emotionally blocked. Threading its way through all this is the story of the dying father who tries to track down his wife after 20 years – an odyssey that finally takes on mythic proportions on the Yangtse River.

In its mix of disciplines, the film often recalls the earlier movies of Zhang Yuan 张元, with whom both Cui (Beijing Bastards 北京杂种, 1993) and Doyle (Green Tea 绿茶, 2002) have worked. Cui’s use of music – from his own songs to orchestral music by Liu Yuan 刘元 and Italian pianist Moreno Donadel – binds together the whole structure rather than dominating it. Yuan’s symphonic score unites with Doyle’s photography to beautiful effect in the Cultural Revolution sections, especially in the performance by real-life dancer Tao Ye expressing his unrequited love for his male friend. It’s one of several cinematic moments that give the film a genuine dramatic power and express visually the sentiments contained in the lateral voiceover by the main character.

Cui’s ambitous script is not all plain sailing. Two subplots, involving a gun-cum-camera the father has invented and the son’s involvement with computer viruses, don’t sit comfortably within the movie; and the character of a wannabe singer (played by Huang Huan 黄幻) who seduces the son is also awkward. But despite its lapses the film does all come together in its finale, which boldly cross-cuts between scenes of a timeless China on the Yangtse with the son, a “lost child born in a lost season”, performing the title rap song in Beijing. The contrast is handled in an uncynical way: despite the movie’s often challenging structure, imagery and editing, Cui, now in his early 50s, espouses traditional values of love, acceptance and forgiveness. It’s as if the rocker-cum-bad boy has finally hit middle age.

The film is also known as Blue Bone, a straight translation of the Chinese title.

CREDITS

Presented by Beijing Antaeus Film (CN). Produced by Beijing Antaeus Film (CN), Beijing East West Music & Art Production (CN).

Script: Cui Jian. Photography: Christopher Doyle. Editing: Zhou Xinxia, Xiao Zhan. Orchestral music: Liu Yuan, Moreno Donadel. Music: Cui Jian. Songs: Cui Jian. Vocals: Zhao Li, Huang Huan, Bei Bei, Jessica Meider. Choreography: Tao Ye. Art direction: Liu Qing. Sound: Hao Gang, Lou Wei. Visual effects: Zhuang Yan (Technicolor [Beijing] Digital Technology). Executive direction: Wen Junkai, Dongfang Xiao, Luo Luo.

Cast: Ni Hongjie (Shi Yanping), Zhao Youliang (Zhong Zhenqing), Yin Fang (Zhong Hua, his son), Lei Han (young Zhong Zhenqing), Tao Ye (Song Hong), Huang Xuan (Chen Dong), Huang Huan (Mengmeng), Guo Jinglin (Xu Tian), Li Jianqiu (Fu Song), Xiong Ruiling (Auntie Zou), Mao Amin (Zhang, music troupe leader), Yu Jianxin (political commissar), Huang Bohan (baby Zhong Hua), Long Shaokang (child Zhong Hua), Zhou Fengyu (young Fu Song), Liu Yuan (The General), Li You (Qian Gui, sound engineer), Wen Junkai, Dongfang Xiao, Hao Gang (investigating committee members), Qiu Ye, Yang Rui (policemen), Xu Mingyue (The General’s son).

Premiere: Rome Film Festival (Competition), 13 Nov 2013.

Release: China, 17 Oct 2014.

(Review originally published on Film Business Asia, 16 Jun 2014.)