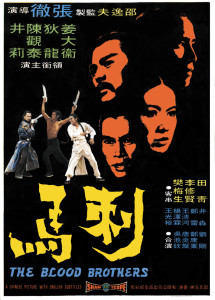

The Blood Brothers

刺马

Hong Kong, 1973, colour, 2.35:1, 117 mins.

Director: Zhang Che 张彻.

Rating: 7/10.

Hubris gets its just desserts in this powerful martial arts drama of male bonding gone wrong.

China, late Qing dynasty, 1870. Zhang Wenxiang (Jiang Dawei) is charged with the murder of Ma Xinyi (Di Long), a general and provincial governor, and writes his confession. Zhang Wenxiang had first met Ma Xinyi when the latter was on his way to fight the (anti-Qing) Taiping rebels. Zhang Wenxiang was then a bandit, along with his god-brother Huang Zong (Chen Guantai), but the confident and scholarly Ma Xinyi inspired them to team up with him to win fame and glory. Huang Zong’s wife, Milan (Jing Li), also accompanied them. They first beat some Shandong bandits, whom Ma Xinyi moulds into a fighting force. Zhang Wenxiang also notices that Ma Xinyi is attracted by Milan. Ma Xinyi leaves them to take his government exams, but two years later writes to them saying he needs men for his army against the Taiping rebels. When the three meet again, however, Ma Xinyi has changed: now a general, he is stiff and formal towards his friends. After beating the rebels, Ma Xinyi is made governor of Jiangxi and Zhejiang, but while they all live in Nanjing love blossoms between him and Milan. While Zhang Wenxiang is away, Ma Xinyi plots Huang Zong’s death. After discovering the plot, Zhang Wenxiang tries to warn Huang Zong but the latter rebuffs him.

REVIEW

On the evidence of the works which have reached this country so far [the UK in mid-1974], the two major producing companies in Hong Kong seem to have markedly different house-styles. Golden Harvest, run by Zou Wenhuai 邹文怀 [Raymond Chow] (who broke away from the Shaw Brothers in 1970 to start his own company), produces about 15 Mandarin films a year, marked by a restraint in blood-letting and runaway imagination, combined with a greater purity in sets, photography and general production values. A typical Golden Harvest budget is about £100,000 – some way above that of their rival, the giant Shaw Brothers. Shao Renmei 邵仁枚 [Runme Shaw] administers their 140-plus distribution outlets from Singapore, while Shao Yifu 邵逸夫 [Run Run Shaw] produces about 40 or so Mandarin films in Hong Kong, each with an approximate budget of about £50,000-60,000. Both the Shaws are past retirement age, but one would hardly guess it from their policy. Shaw martial arts films are in direct contrast to the Golden Harvest pictures: slaughter, wholesale and bloody, is a hallmark, while elaborate sets, dark colour schemes, and dramatic use of the camera are all freely employed. Whereas the Golden Harvest films (the pictures by Li Xiaolong 李小龙 [Bruce Lee], and Hap Ki Do, for example) try, within the general scheme of things, to remain partly believable by not introducing superhuman skills or gravity-defying feats, the Shaw Brothers’ productions opt for all-out fantasy, with the heroic image writ large upon the screen. Though aerial leaps are a common feature of both studios’ productions, in the Shaw films they attain magical qualities (Intimate Confessions of a Chinese Courtesan 爱奴, 1972; Golden Swallow 金燕子, 1968) rather than strictly practical; with the Shaws we are shown super-heroes, myths made flesh, men and women with unique, individual powers who are, by nature, in permanent contest with each other. Visually, Shaw films are unmistakable: deep reds and blacks (clothes, lanterns, blood) are given precedence over all other colours, while others are picked for their overt signalling qualities (white, gold); compositions are crowded with detail and persons, while house sets are warren-like with passageways and streets; photography is frequently under-lit (unlike the bright Golden Harvest visuals), giving the Shawscope process little depth of field – focus is therefore often shaky, and the dim lighting gives colours a rich, menacing quality; dramatic use is also made of sudden zooming and abrupt focus pulls, while single deaths are often shot in slow-motion with a prolonged gurgling death-rattle on the soundtrack. The differences between the two studios should now be obvious: everything, in the Shaw films, is brought to bear on the central issue – the dark and bloody business of super-heroes in action.

All the best of the Shaws’ house-style can be seen in The Blood Brothers 刺马 [released in the UK as Chinese Vengeance], a remarkably effective picture going the rounds [in a double bill] with the equally prestigious The Master of Kung Fu 黄飞鸿 [released in the UK as Death Kick]. Set in the closing years of the Qing dynasty, The Blood Brothers is a costume martial arts film, unfolding in an elaborate flashback format and capped by a somewhat equivocal moral ending. Zhang Wenxiang gives himself up after murdering the Provincial Governor Ma Xinyi: on his knees before a court of trial, he freely writes a long confession in which the past unfolds. The film traces the relationship between three warriors who meet one day on a country road: Zhang Wenxiang and his brother-in-law Huang Zong ambush Ma Xinyi, and after prolonged fighting each recognises the other’s skills. Finally the three become blood-brothers and together crush a revolt against the Emperor. Ma Xinyi leaves to take the final part of his Army exams, and some years later calls the other two to his side to fight under his banner; but Ma Xinyi is a changed, ambitious man, and having fallen in love with Milan, Huang Zong’s wife, he sets about exterminating his two friends. Zhang Wenxiang catches on, and in single combat, kills Ma Xinyi.

All the martial arts films, from whatever factory, deal in clear-cut moral basics: good, bad, revenge, honour, and so on. The Shaws’ films are rather more complex than others, their rich, decadent style complementing their views that there is no clear border between good and bad. Life is cheap, and no one is unexpendable. Ma Xinyi is quite obviously the better fighter of the three friends but, not for the first time in a Shaw film, he possesses dubious morals (compare Silver Roc in Golden Swallow). Everyone pays in the end: Ma Xinyi for the murder of Huang Zong, his love for Milan and his dangerous hubris; Huang Zong for distrusting his brother-in-law’s advice about his safety (i.e. more hubris); and Zhang Wenxiang for his killing of Ma Xinyi and original attack at the start of the flashback. The Blood Brothers is particularly ruthless in its appropriation of justice, the only clear message being that pride and hubris are to be punished; the fact that Zhang’s heart is cut out at the end by equally amoral characters adds to the general pessimism found in most Shaw productions.

Technically, the film has many good features, not least the music by Chen Yongyu 陈永煜 [aka Chen Xunqi 陈勋奇/Frankie Chan] and the photography by Gong Muduo 龚幕铎 [aka Japan’s Miyaki Yukio /宮木幸雄]: the duel between Ma and Zhang is set in a high, windswept compound, the frame (for once) almost bare of detail; combat sequences, but especially that of Ma training Zhang’s men to fight, are handled nimbly and neatly. Naturally, the ludicracies mount as the film progresses, climaxing in Ma receiving two daggers in the stomach prior to fighting his duel; this, however, is standard Shaw sign-language for the principal character – expecting no quarter from others, his own death is always bloody and prolonged. Zhang’s execution provides the film’s climax: superimposition of past events, heavenly choirs, and golden sunsets all melt into a sublime example of cod transfiguration. Once again, the mythic idea triumphs over all the film’s shortcomings in taste, presentation and dubbing.

CREDITS

Presented by Shaw Brothers (HK). Produced by Shaw Brothers (HK).

Script: Ni Kuang, Zhang Che. Photography: Gong Muduo [Miyaki Yukio]. Editing: Guo Tinghong. Music: Chen Yongyu [Chen Xunqi/Frankie Chan]. Art direction: Cao Zhuangsheng [Johnson Tsao]. Costumes: Li Qi. Sound: Wang Yonghua. Action: Tang Jia, Liu Jialiang.

Cast: Jiang Dawei [David Chiang] (Zhang Wenxiang), Di Long (Ma Xinyi), Chen Guantai (Huang Zong), Jing Li (Milan, Huang Zong’s wife), Tian Qing (Ma Zhongxin), Li Xiuxian [Danny Lee] (Zeng Tianyang), Fan Meisheng (Yan, mountain bandit leader), Jing Miao (judge), Wang Qinghe (assistant judge), Yang Zelin (Li Wen), Wang Guangyu, Liu Gang, Zheng Kangye, Tang Yancan (Ma Xinyi’s henchmen).

Release: Hong Kong, 24 Feb 1973.

(Review section originally published in UK monthly films and filming, Sep 1974, as Chinese Vengeance. Modern annotations in square brackets. Read the review of The Master of Kung Fu here: https://sino-cinema.com/2015/12/10/archive-review-the-master-of-kung-fu-1973/.)