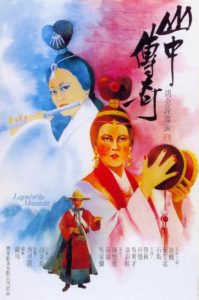

Legend of the Mountain

山中传奇

Hong Kong, 1979, colour, 2.35:1, 193 mins. (international version), 125 mins. (local release version).

Director: Hu Jinquan 胡金铨 [King Hu].

Rating: 9/10.

A Song dynasty scholar is seduced by two competing female spirits in this elegant, self-assured masterwork by Hong Kong-based Hu Jinquan [King Hu].

Northwestern China, Song dynasty, 11th century AD. Scholar He Yunqing (Shi Jun), who failed the official exams and has been doing odd jobs for money until he finds a more permanent post, is offered some work by Haiyin temple to make a copy of the Mudra sutra, a powerful manual that can reincarnate and save wandering souls. The sutra is needed in the capital for a ceremony of remembrance for soldiers who died in a war near the border with the Western Xia. He Yunqing doesn’t believe in Buddhism or ghosts but does it for the money. After collecting the four volumes of the sutra from the temple, he sets off to stay with Cui Hongzhi (Tong Lin) at North Fort, in Qinfeng pass, as recommended by Huiming (Lu Chun), a novice Buddhist monk at the temple. An army staff officer now with time on his hands, Cui Hongzhi is a friend of Huiming, who says he is also a cultured man and will make sure He Yunqing gets the quiet he needs. After walking all day, He Yunqing dozes off at a remote pavilion but is woken by a passing woodcutter (Wu Jiaxiang), who says North Fort is now abandoned but still shows him the way. En route He Yunqing sees a young woman flautist in the distance, but she suddenly disappears. Next day, on arriving at the fort, he thinks he sees the same flautist a couple of times, but she always vanishes. Cui Hongzhi welcomes him and explains that the fort was abandoned after a peace treaty was signed with the Western Xia, so now there is only him and his crazed servant Zhang (Tian Feng). He gives He Yunqing the quarters of one of the concubines of the late high commissioner, Han (Sun Yue). Mrs. Wang (Xu Caihong), Han’s former housekeeper, appears and offers to do He Yunqing’s cooking and laundry in exchange for him tutoring her daughter, Yue Niang (Xu Feng) – a proposal He Yunqing says he can’t accept as he has no experience of teaching. Hoping to sweet-talk him into agreeing, the pushy Mrs. Wang invites He Yunqing, along with Cui Hongzhi, to dinner that evening, where the scholar is introduced to Yue Niang. Midway through dinner, a lama (Wu Mingcai), whom He Yunqing believes has been following him, turns up at the front door but is shooed away by Yue Niang. The combination of Yue Niang’s hypnotic drumming and Mrs. Wang’s 10-year-old wine makes He Yunqing pass out. Next morning he wakes up back at the fort, where Yue Niang serves him tea. He remembers nothing; but she says they spent the night together, during which He Yunqing pledged his love for her. He agrees to do the decent thing and get married; he tells Mrs. Wang he has no money, but she is unfazed. He Yunqing and Yue Niang marry. Then one day, while visiting a nearby wine house owned by Mrs. Zhuang (Jeon Suk), a friend of Cui Hongzhi, He Yunqing is struck by the likeness of her daughter, Zhuang Yiyun (Zhang Aijia), to the elusive flautist he kept seeing on his journey.

REVIEW

There is a self-assurance and sheer formal elegance about Legend of the Mountain 山中传奇 which is quite breathtaking, and if, as appears likely with his next project, director Hu Jinquan 胡金铨 [King Hu] intends taking a rest from costume adventures, Legend will serve nicely as a neat summing-up of a decade-and-a-half of explorative film-making. It is particularly apt, too, because it is not primarily a martial arts film: a brief flurry of fighting appears at the end, as a resolution of pent-up tensions, but Legend is otherwise firmly in the tradition of the Chinese “ghost” story. Hu did not start his directorial career as a martial arts specialist (although he has since made his fame and fortune in that field) and even today stresses that he knows little about the field; what he has always been interested in, however, is the dividing line between appearance and reality, especially as regards the Buddhist and Daoist philosophies, and the illusory nature of complex power-structures. In this respect, Legend is perfect material, dispensing with the need for martial arts every few reels (magical as these always are in Hu’s films, and famous as they have become, I feel his true forte lies more in the sequences of character interplay which lie between) and able to contemplate the central mystery at leisure.

Legend headlined particularly strong Hong Kong representation at the 1979 London Film Festival, and was shot back-to-back over an arduous schedule with Raining in the Mountain 空山灵雨 (which perfects the worlds of The Fate of Lee Khan 迎春阁之风波, 1973, and A Touch of Zen 侠女, 1970-73, but does not break new ground like Legend). After hunting locations in South Korea during May and June of 1977, Hu started shooting both films that August, finally halting early the following year due to the extreme cold; shooting resumed in April and was completed by September. Weather throughout was unpredictable and the shooting sites were often in inaccessible locations; half the crew was Korean and could not speak Chinese; one actor went down with TB, another was injured in a car crash, Hu himself suffered malnutrition, the first production manager left halfway in sheer desperation, and everyone’s patience was stretched by bureaucratic delays and communication difficulties. It is a wonder that none of this shows and that each of the two films has such a separate character (the casts are almost identical): by Chinese standards Hu’s budgets were very large, and his shooting schedule immense, but the wait has been more than worthwhile.

The story, by Hu’s wife Zhong Ling 钟玲, is an amplification of a Song dynasty short story [by an unknown author], A Cave of Ghosts in the Western Mountain 西山一窟鬼 – although to describe the picture simply as a “ghost story” would be to miss the many inflexions which this literary term possesses in Chinese. There is a magical – and often benevolent – aspect to the Chinese ghost story which is generally missing in western equivalents; and, although Chinese “ghost” literature has its fair share of vampires, gore and horror, it is the more spiritual aspects which are of concern in Legend. The formula is a tried and trusted one in Chinese literature: the figure of the impressionable young scholar attracted by a young woman-cum-wandering spirit who beseeches his help (Shi Jun 石隽, who plays him here, starred in a similar story, Ghost of the Mirror 古镜幽魂, 1974); the extra wrinkle here is that he is later approached by another young woman with the self-same request for spiritual salvation (by snatching a Tantric sutra he has been commissioned to copy, which guides souls to their next incarnation). The moral flux generated between the evil Melody (who hypnotises him with her playing on a hand drum) and the benevolent Cloud (who first appears playing her bamboo flute) spins a web of confusion around the baffled young scholar as complex as any of the intrigues in Hu’s Lee Khan or Dragon Inn 龙门客栈 (1967). It is a nice touch to make the scholar a figure of only moderate skills: the script notes at the beginning that he failed his civil service examinations and was on the look-out for work when offered the job of making a fair copy of the sutra – Hu’s “hero” is this as fallible as the one in A Touch of Zen (also acted by Shi), and as suitably open to suggestion as is necessary for the plot.

The majority of the film’s imagery is dedicated to evoking the spirit of Daoist philosophy – the natural order of things, and such Daoist symbols as running water and nature in bloom. From the film’s main title, through the journey of the scholar to his work retreat, the viewer is treated to a dazzling display of light, landscape and liquid imagery which serves both to establish the film’s surreal plane of activity as well as to stress the action’s complete withdrawal from populated society: as in most of Hu’s films, the plot is set in a deserted no-man’s-land, in this case on the borders of [north]western China. Later, the scholar’s wedding to Melody is celebrated in Daoist imagery of nature in full bloom; and, during the long flashbacks which explain the rivalry between Melody and Cloud (as flautist concubines of High Commissioner Han), their respective musical skills are separately characterised through images of nature at work (Melody by birds and frogs; Cloud by brighter and less menacing images of squirrels, waterfalls and seagulls). Here, as throughout the film, the stunning colour photography of Chen Junjie 陈俊杰, one of Hong Kong’s finest young cameramen (with notable work on the recent The Servants 墙内墙外, 1979, too), scores time and time again; occasional filter effects are clumsy but the quality of the colour puts many a western film firmly to shame and celebrates Hu’s impeccable art direction at every turn. The latter, correct even to the smallest brush-tip, impregnates the material in often forceful ways: the contrast between the softer colourations of Cloud’s clothes and the harder lines of Melody’s make-up become more pronounced as their different natures are laid bare – and there is a devastating change of costume for Melody (striking red on white) when she appears, mask of meekness finally cast aside, for the crucial duel of magic between her and the lama priest.

The talents of Taiwan actress Xu Feng 徐枫 have been sufficiently praised by me in reviews of past Hu films; little need be added here except to say that she handles her transformation from charm to open malevolence with stunning authority. Zhang Aijia 张艾嘉 [Sylvia Chang], in (for her) a rare period role, is a neat foil; although her role suffers from being somewhat under-written, she brings the same quality of quiet determination to Cloud as she did to Lin Daiyu in The Dream of the Red Chamber 金玉良缘红楼梦 (1977, dir. Li Hanxiang 李翰祥), completed just before she started work on Legend. Shi, in a familiar role as the hapless scholar, is particularly good in the light-comedy sequences which punctuate the action, mostly involving his forceful mother-in-law Mrs. Wang (played with relish by Xu Caihong 徐彩虹, and dubbed with a man’s voice).

Let us hope that it will not be too long before Legend is released in the UK – and not in the marginally trimmed one [186 mins.] which appeared at the London Film Festival (in which the cuts merely served to unbalance certain sequences and break the film’s rhythm). There are few enough film-makers with the vision and substance to fill three-hour canvases without dawdling, à la Francis Ford Coppola or Michael Cimino, and Hu has once again proved not only that he ranks among them but also that he is master of his material yet.

CREDITS

Presented by Prosperity Film (HK).

Script: Zhong Ling. Photography: Chen Junjie. Editing: Hu Jinquan [King Hu], Xiao Nan. Music: Wu Dajiang. Art direction: Hu Jinquan [King Hu]. Costume design: Hu Jinquan [King Hu]. Action: Wu Mingcai.

Cast: Xu Feng (Yue Niang/Melody), Zhang Aijia [Sylvia Chang] (Zhuang Yiyun/Cloud), Shi Jun (He Yunqing, scholar), Tong Lin (Cui Hongzhi), Tian Feng (Zhang, crazy man), Wu Mingcai (lama), Xu Caihong (Mrs. Wang), Chen Huilou (Yang, Daoist priest), Sun Yue (Han, high commissioner), Wu Jiaxiang (woodcutter), Lu Chun (Huiming, novice Buddhist priest), Gim Mun-jeong (Xiaoqing, Mrs. Wang’s servant), Jeon Suk (Mrs. Zhuang, Zhuang Yiyun’s mother), Gim Chang-geun (Fa Yuan temple master).

Premiere: Toronto Film Festival (Gala Presentations), 13 Sep 1979.

Release: Hong Kong, 4 Oct 1979 (125-min. version).

(Review section originally published in UK monthly films and filming, Feb 1980. Modern annotations in square brackets.)