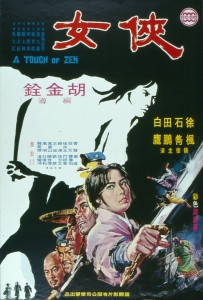

A Touch of Zen

侠女

Taiwan, 1970-73, colour, 2.35:1, 177 mins.

Director: Hu Jinquan 胡金铨 [King Hu].

Rating: 8/10.

Costume martial-arts classic is an elaborate chess game poised between the real and the supernatural.

A small town, somewhere in Shaanxi province, central China, the Ming dynasty (AD 1368-1644). Gu Shengzhai (Shi Jun), a scholar and portrait painter in his 30s, lives on the edge of town in part of the abandoned Jing Lu Fort 靖虏屯堡 with his mother (Zhang Bingyu), who is always nagging him about getting married and sitting the exam for government service. One day they discover a young woman in her early 20s, Yang Huizhen (Xu Feng), and her sick mother have moved into another part of the fort. One of Gu Shengzhai’s customers, Ouyang Nian (Tian Peng), starts asking questions about her, and Gu Shengzhai finally meets her. Yang Huizhen turns down a proposal of marriage but she finally spends a night with Gu Shengzhai. The next day she is attacked by Ouyang Nian but fights him off. Afterwards she explains to Gu Shengzhai that her family was massacred by the Eastern Depot – a secret police network controlled by court eunuchs – after her father (Jia Lushi) sent a critique of the group to the emperor. Helping her to escape were two generals, Shi Wenqiao (Bai Ying), now disguised as a blind fortune teller, and Lu Ding’an (Xue Han), now disguised as a herbalist doctor, plus their martial-arts master Hui Yuan (Qiao Hong), a Buddhist high priest. Gu Shengzhai helps Yang Huizhen and her comrades to devise a plan to ambush the Eastern Depot’s soldiers, led by Men Da (Wang Rui), around the supposedly “haunted” fort. The deception goes well but Lu Ding’an is killed. Yang Huizhen and Shi Wenqiao disappear, to Hui Yuan’s monastery in the mountains. Some time later Gu tracks down her whereabouts, and is confronted with a surprise.

REVIEW

If Chinese cinema first gained major attention in the West through Li Xiaolong 李小龙 [Bruce Lee] and the martial arts films, then it is slowly gaining its “artistic respectability” through the films of Hu Jinquan 胡金铨 [King Hu], particularly with the major breakthrough of Hu winning the Grand Prix Technique at Cannes last year [1975] for the above film. A Touch of Zen 侠女 was shown at the 1975 London Film Festival (when I briefly wrote about it in the February [1976] films and filming [see below]) and the majority of British critics, faced with a giant reversal of expectations after the more commonplace dubbed martial arts pictures, reacted in a general confusion of sub-Japanese dismay. Thankfully, the enterprising new company Seven Keys (who distribute the American Film Theatre series and who will show Hu’s latest work, The Valiant Ones 忠烈图, 1975, this autumn) have placed it in general distribution [in the UK]. Hu is said to have removed two minutes from the complete version, for artistic reasons, but since it is impossible to notice the missing footage I have given the full running-time above. The Screen on Islington Green [an arthouse in North London] have given it its public premiere, and it should now be in demand throughout the country. A Touch of Zen runs a close-run fight with The Fate of Lee Khan 迎春阁之风波 (1973) for the distinction of being Hu’s most accomplished work so far; the latter is a sublime conclusion to his trilogy of “inn films”, while the former is a lengthier and fuller statement of his interest in the clash of the real and supernatural in a philosophical context.

A few words might be in order for those who do not know of the film’s tortuous history. In 1965, after leaving Shaw Brothers, Hu joined Union Film 联邦影业 set up by Xia Wu Liangfang 夏吴良芳, almost singlehandedly hiring new talent, training it, building the studio, etc. Many names now famous in Hong Kong cinema date from this time and are Hu alumni. After making the second of his “inn films” Dragon Inn 龙门客栈 (1967), which was a vast commercial success in Southeast Asia, Hu started on A Touch of Zen, an elaborate treatment of a tiny short story by the Ming dynasty scholar Pu Songling 蒲松龄 [in his 1740 collection known in English as Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio 聊斋志异]. The title of the story, 侠女 (which is also that of the film – meaning roughly The Gallant Girl), refers to the central character of Yang Huizhen, and the film’s English title reflects the philosophical bent which Hu placed on the original. The main set for the film took about nine months to construct [at a reported cost of NT14 million], and has subsequently been hired out for hundreds of other pictures: Hu is famed for his painstaking efforts and slow rate of filming – the 10-minute-long fight in the bamboo forest took 25 days to shoot – and, in all, A Touch of Zen was about two years in the making. The producer, behind Hu’s back, cut the film down to two hours for release and it flopped. Eventually, Hu reconstructed the original and screened it at Cannes. Since that experience he has worked independently. [See below for the film’s precise chronology.]

A Touch of Zen is set in a small town in Shaanxi province during the Ming dynasty (AD 1368-1644), an era of relative calm after the Mongol Yuan dynasty (during which The Fate of Lee Khan is set) but characterised by growing corruption at court and the establishment of a lethal secret service, the Eastern Group [aka Eastern Depot/Eastern Chamber 东厂], which was to all intents and purposes under the control of court eunuchs. Artistically it was the age of the “gentleman scholar” in the provinces, since the stultifying centralisation of power had led to an imperial delight in sheer academicism. The central character of the film reflects this artistic devolution: Gu Shengzhai is a retiring scholar of about 30 who earns a living from portrait painting, and is continually nagged by his mother, with whom he lives, for not “furthering” himself by marrying and joining the imperial service. Into his quiet existence come a variety of weird and wonderful characters, and it is from the tangential experiences of Gu Shengzhai with their special world that the film draws the majority of its excitement. For the first hour Hu keeps his audience in a state of ignorance, only imparting information as the somewhat befuddled central character learns of it. This suspension of normality – a slight dislocation of reality (akin, in a different context, to that of Roman Polański) – is Hu’s most pervasive trademark, and is developed to its fullest extent in A Touch of Zen. Round about our modest “hero” burst sudden flurries of intrigue and action, often barely glimpsed in the frame: Hu manipulates his audience at every step, causing a metaphorical pause to scratch the head, and only after careful preparation is the full story divulged.

Chief amongst the strangers is Yang Huizhen, a 20-year-old girl who settles in the deserted (and supposedly haunted) Jing Lu Fort outside town. When another stranger [Ouyang Nian] who commissions Gu Shengzhai to paint his portrait starts asking questions, Gu Shengzhai slowly becomes curious and, at his mother’s urgings (smelling a marriage in the air), finally visits her. Eventually Yang Huizhen offers herself to Gu Shengzhai one night, and only after a sudden attack by the stranger, Ouyang Nian, does Gu Shengzhai learn the truth about her and her two accomplices [generals Shi Wenqiao and Lu Ding’an, disguised as a fortune teller and a herbalist doctor]. One layer of the film is immediately peeled off as the three strangers reveal their true identities (fugitives from the Eastern Group), and Gu Shengzhai’s scholarship now joins with their professional skills to ward off the impending attack of Ouyang Nian’s superior, Nie Qiu: Gu Shengzhai’s mother spreads the rumour that the fort is haunted and the four rig the place with automatic weapons and surprise devices. Next morning, Gu Shengzhai finds himself alone, as if all that had gone before was a dream; only after many months does he trace Yang Huizhen to the monastery of high priest Hui Yuan, finding their child waiting for him on the rocks below with a note from Yang Huizhen saying that he can never see her again. On the way back, however, Gu Shengzhai and the baby are pursued by the head of the Eastern Group, Xu Xianchun, and it is only with the fortuitous arrival of Yang Huizhen, Shi Wenqiao and the high priest that Xu Xianchun is defeated. In fake submission Xu Xianchun catches the high priest off-guard and stabs him; the priest achieves nirvana before the eyes of all.

In essence, the film divides into two parts, the first ending after 145 minutes with Gu Shengzhai collecting his child at the foot of the monastery. It is a supremely moving moment, typifying the work’s basic notion that Gu Shengzhai exists on a separate plane to Yang Huizhen, Shi Wenqiao and the like, never the twain to meet. In retrospect, Yang Huizhen’s unexpected decision to offer herself to him can be seen merely as a desirable tactic, for there never exists any true relationship between the pair. Yang Huizhen , Shi Wenqiao and Lu Ding’an (all trained in the martial arts by the priest Hui Yuan several years ago) are always aware of their elitist existence, and certainly their contact with Gu Shengzhai leaves nothing like the mark that it leaves on him. The break at this point [in the film] is so marked that the second part, which is entirely composed of two super-combats with Xu Xianchun, seems ill-balanced, and is the film’s one major weakness. Hu here seems to rush his fences, and the final scenes, in which the priest bleeds gold before the startled onlookers, is protracted beyond its point. This apart, however (and who would not expect a few faults in a three-hour work), A Touch of Zen shows all the signs of meticulous gradation. Hu’s films are very much cinematic onions, each layer giving way to something far richer and more unseen; successive viewings of his works reveal further riches and subtleties in a way that not many other directors can offer. A Touch of Zen, for instance, starts by plunging its audience into a state of ignorance and, under the guise of feeding it more information, actually leads it into a deeper state of ignorance than when the film began. This is the progression hinted at in the English title (chosen by Hu himself), which promises a touch of zen rather than zen itself – a taste of the unknown, a tangential experience of it (like Gu Shengzhai), rather than zen itself in one blinding flash. As such, the work is something of an elaborate game, with the audience as the dummy (compare, in modern literature, John Fowles’ very similar exercise with The Magus): for the first hour we sense that much is going on beyond our ken, and even after being told the true identities of the principals, the rug is pulled still further from under our feet by the rigged fort – next morning Gu Shengzhai surveys his war-machines, laughing out aloud at himself (and the techniques of cinema which had made the preceding reel so exciting), but the laugh is again on him when he discovers that Yang & Co. have fled with the dawn.

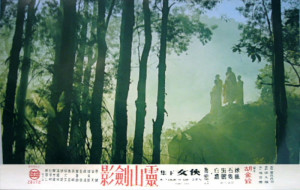

It is clear that Yang Huizhen is only half-way up the pyramid of power: at the top sits the high priest, possibly the only one able to deal with a fellow specialist like Xu Xianchun. The priest’s devastating powers, which he uses to play with Xu Xianchun like a child, are only ever hinted at by the film, which generally resorts to complementary imagery such as the sun, or Daoist parallels like flowing water and flora, for effect. Just as Hu’s films are elaborate chess-like games, so are they also demonstrations of technique. Technique figures greatly in the present work, and is marshalled at important moments in direct service of the film’s message. The very first image is of a spider trapping its victime in a web at night, and throughout Hu is mindful of the importance of various coups-de-cinéma: the introduction, in a flashback, of the priest and his monks, demonstrating their powers with a ghastly ease and calmness; the fight in the bamboo forest, with sunbeams and rising condensation creating a special atmosphere; the magical appearance at the end of the priest and his monks when Yang Huizhen and Shi Wenqiao are hard-pressed defending Gu Shengzhai (Yang Huizhen and Shi Wenqiao are relegated to the position of merely awed spectators from then on); even the use of multi-screen when Gu Shengzhai’s mother spreads the rumour that the fort is haunted. These coups form waves in a perpetually restless sea, for Hu never allows the story to ferment. What is shown on-screen is generally perfectly real, but (as, for instance, with [the films of Hungarian director Miklós] Jancsó) one feels the presence of greater powers at work; only at the end do we catch a glimpse of these at first-hand. Elsewhere, Hu’s technique suggests: the camera tracking slowly in long-shot, subliminal editing in the combat sequences, important action outside or on the edge of the frame. And suddenly that moment of stillness which signifies imminent danger.

As the eponymous heroine, Xu Feng 徐枫 [then still in her late teens] is spectacularly good amongst proven talent: her capacity for suggesting a remote sexuality residing within those misty eyes without at all sacrificing her elegant toughness remains quite unique. Bai Ying 白鹰 (like Xu, still at an early stage in his film career, and a Hu regular) makes a dependable partner, and Han Yingjie 汉英杰 (probably best known as the villain in The Big Boss 唐山大兄, 1971) effortlessly incarnates the Eastern Group chief. Outclassing all, however, in sheer majesty – a fine counterweight to the somewhat bumbling Shi Jun 石隽 as Gu Shengzhai – is Qiao Hong 乔宏 [Roy Chiao] as the high priest. With this actor, each twitch becomes a threat, each movement a positive danger to existence; in him resides the film’s core of meaning to which Qiao rises superbly.

CREDITS

Presented by Union Film (TW). Produced by International Film (TW).

Script: Hu Jinquan [King Hu]. Short story: Pu Songling. Photography: Hua Huiying. Assistant photography: Zhou Yexing. Editing: Hu Jinquan [King Hu], Wang Jinchen. Music: Wu Dajiang. Guqin direction: Hou Jizhou. Song: Luo Mingdao. Art direction: Chen Shanglin, Hu Jinquan. Set decoration: Zou Zhiliang. Costumes: Li Jiazhi. Action: Han Yingjie, Pan Yaokun.

Cast: Xu Feng (Yang Huizhen/Yang Zhiyun), Shi Jun (Gu Shengzhai), Qiao Hong [Roy Chiao] (Hui Yuan, high priest), Bai Ying (Shi Wenqiao, general), Tian Peng (Ouyang Nian), Cao Jian (Xu Zhengqing, local magistrate), Miao Tian (Nie Qiu, eunuch’s deputy), Zhang Bingyu (Gu Shengzhai’s mother), Xue Han (Lu Ding’an, general), Wang Rui (Men Da), Wan Zhongshan (Lu Qiang), Gao Ming (Huaiyuan county clerk), Lu Zhi (jinyiwei – military secret policeman), Jia Lushi (Yang Lian, grand censor, Yang Huizhen’s father), Han Yingjie (Xu Xianchun), Hong Jinbao [Sammo Hung], Chen Huiyi (Xu Xianchun’s sons), Hao Lvren (old woodcutter), Chen Shiwei, Du Weihe (Men Da’s bodyguards), Lin Zhengying, Cheng Long [Jackie Chan], Wu Mingcai, Shan Mao, Long Fei, Li Kui, Xu Qingchun (Eastern Depot men), Xie Zhongmou (eunuch messenger), Liu Chu (jinyiwei – military secret policeman), Chen Shaolong, Chen Mingwei, Qi Haozhao, Yang Shijun (Hui Yuan’s monks), Zhang Yunwen (Huaiyuan county government office official), Men Juhua, Liu Youbin, Pan Yaokun.

Release: Taiwan, 10 Jul 1970 (part one), 3 May 1973 (part two).

(Review section originally published in UK monthly films and filming, Aug 1976. Modern annotations in square brackets.)

Earlier Thoughts on A Touch of Zen

No less thrilling [than The Texas Chain Saw Massacre] but considerably more magical was A Touch of Zen by Hu Jinquan 胡金铨 [King Hu] – only recently reconstructed in its full version by the director. I shall be dealing with Hu’s works in greater detail in an article later this year (and the National Film Theatre [in London] is doing its best to organise a retrospective), but it is worth stressing now the woeful lack of appreciation of his works in anything other than sub-Japanese terms by all but a handful of critics in this country [the UK]. Hu is not the greatest thing from Hong Kong since take-away meals, but he is certainly in the top flight of Chinese directors in any field. His idiom, while paraphrasing Hong Kong cinematic conventions in more “European” terms, remains thoroughly Chinese, and A Touch of Zen 侠女 is his most cohesive and assured statement to date. The temptation to confuse Chinese and Japanese cultures is only part of the general ignorance towards Hong Kong film-making; the similarities are few and far between, and one suspects that Hong Kong’s propensity for flamboyance is a major stumbling block towards so-called critical acceptance. A Touch of Zen tantalises the senses for almost three hours in a moto perpetuo of intrigue, subliminal combat, conflicting philosophies, and shifting loyalties. Hu’s film works on a variety of levels, from the most obvious to the labyrinthine, and his trademark (a feeling of dislocated reality) is splendidly in evidence during the long “prologue” in which the main character, like the audience, is held in a suspension of disbelief and ignorance. Superb performances from Xu Feng 徐枫 (as the Gallant Girl of the film’s Chinese title), Bai Ying 白鹰, and Qiao Hong 乔宏, plus exquisite photography by Hua Hui-ying 华慧英. But more of that anon.

(Extract from article Curiouser and…Curiouser: Some Underrated Rarities from the 19th London Film Festival, published in UK monthly films and filming, Feb 1976. Modern annotations in square brackets. In the event, the NFT’s retrospective never happened, due to a combination of rights and print problems at the time. Neither did my own article on Hu in films and filming; instead, I wrote a study of Hu’s career for International Film Guide 1978 [published in autumn 1977], in which he was one of the five Directors of the Year. See here: https://sino-cinema.com/2016/05/21/people-hu-jinquan/.)

The Chronology of A Touch of Zen

Shooting started on 13 Dec 1967 but dragged on for two years with no end in sight. Exasperated by the slowness of Hu Jinquan 胡金铨 [King Hu] and wanting to get some return on investment, the producers released “part one” of the film, under the title A Touch of Zen 侠女上集, in Taiwan on 10 Jul 1970. Running about 100 minutes, and ending with the title character swooping down from the trees at the climax of the bamboo-forest fight, it ran for over a month, until 20 Jul 1970. After Hu

Shooting started on 13 Dec 1967 but dragged on for two years with no end in sight. Exasperated by the slowness of Hu Jinquan 胡金铨 [King Hu] and wanting to get some return on investment, the producers released “part one” of the film, under the title A Touch of Zen 侠女上集, in Taiwan on 10 Jul 1970. Running about 100 minutes, and ending with the title character swooping down from the trees at the climax of the bamboo-forest fight, it ran for over a month, until 20 Jul 1970. After Hu  finally finished shooting five months later, in Dec 1970, the producers prepared a two-hour version of the material, under the title A Touch of Zen 侠女, which was released in Hong Kong on 18 Nov 1971. It ran for two weeks, closing on 1 Dec 1971 and grossing HK$678,000 – certainly not the disaster of popular mythology, but nothing special for a production of that size. A year and a half later, A Touch of Zen: Part Two 侠女下集 灵山剑影 (literally, “Spirit, Mountain, Sword, Shadow”) was released in Taiwan. It began with a re-cap of the fight in the bamboo forest and ran about 90 minutes. Opening on 3 May 1973, it played for only a week, closing on 11 May.

finally finished shooting five months later, in Dec 1970, the producers prepared a two-hour version of the material, under the title A Touch of Zen 侠女, which was released in Hong Kong on 18 Nov 1971. It ran for two weeks, closing on 1 Dec 1971 and grossing HK$678,000 – certainly not the disaster of popular mythology, but nothing special for a production of that size. A year and a half later, A Touch of Zen: Part Two 侠女下集 灵山剑影 (literally, “Spirit, Mountain, Sword, Shadow”) was released in Taiwan. It began with a re-cap of the fight in the bamboo forest and ran about 90 minutes. Opening on 3 May 1973, it played for only a week, closing on 11 May.

Two years later, in 1975, Hu raised the money to buy the film’s US and European rights and put together a three-hour “international” version – basically the two Taiwan parts stitched together, minus the overlap of the bamboo-forest fight – which was screened at the Cannes Film Festival on 21 May, as part of the Official Competition. (The only other East Asian film in competition was Pastoral Hide and Seek 田園に死す by Japan’s Terayama Shuji 寺山修司.) The jury, headed by French actress Jeanne Moreau, did not give it any prize; but it won the Grand Prix Technique (Technical Grand Prix), awarded by a separate jury appointed by the CST, France’s association of film and TV technicians. On 13 Aug that year, a 130-minute version, edited by the producers, opened in Taiwan and ran for two weeks, closing on 29 Aug. Two months later it ran for three more days, 21-23 Oct. The following year the two-hour Hong Kong version was re-released by the producers but ran for only four days (16-19 Mar 1976), grossing a mere HK$56,000. Meanwhile, Hu’s “international” version was sold internationally and played at various festivals, including London in 1975, New York in 1976 and Toronto in 1977.

D.E.