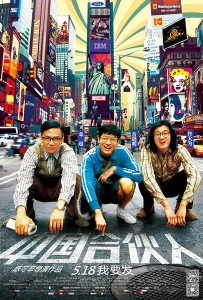

American Dreams in China

中国合伙人

Hong Kong/China, 2013, colour, 2.35:1, 112 mins.

Director: Chen Kexin 陈可辛 [Peter Chan].

Rating: 7/10.

Long-limbed tale of three friends in business together boasts strong lead performances.

China, 2003. Beijing-based New Dreams language school – founded by Meng Xiaojun (Deng Chao), Wang Yang (Tong Dawei) and Cheng Dongqing (Huang Xiaoming) – is being sued by New York’s EES for allegedly stealing its TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) exam papers to give New Dreams’ students an advantage in applying to US universities. Back in 1980, the three had met at Yanjing University in Beijing. The most ambitious was Meng Xiaojun, who was dating Liang Qin (Wang Zhen); his grandfather had gained an English degree in the US and he was obsessed with following in his footsteps. Cheng Dongqing was romancing fellow student Su Mei (Du Juan), while Wang Yang was seeing an  American girl, Lucy (Claire Quirk). Meng Xiaojun passed his TOEFL exam and got a US student visa, vowing never to return to China now he had an opportunity to pursue his dream. Cheng Dongqing, however, was rejected and stayed on as a university teacher. By 1988, Cheng Dongqing was married to Su Mei and giving private English lessons in addition to doing his university job. But when Su Mei left for the US after she got a visa, and Lucy returned home, Cheng Dongqing and Wang Yang were left alone. By 1992, China’s economy was starting to boom; but in the US, Meng Xiaojun, now married to Liang Qin, was fired from his job in a lab. The following year, Su Mei called Cheng Dongqing from the US and said she wanted to break up; subsequently, Cheng Dongqing was sacked from YJU’s Foreign Languages Faculty for his unauthorised private teaching. He and Wang Yang started a private school in an abandoned factory to feed the demand for English lessons and made a ton of money. In 1994, Meng Xiaojun returned from the US, with his tail between his legs, and joined the other two in the school, contributing his experience of what Americans want. They named the school New Dreams, moved into new premises and became the largest private school in China. But business differences between the three started to divide them.

American girl, Lucy (Claire Quirk). Meng Xiaojun passed his TOEFL exam and got a US student visa, vowing never to return to China now he had an opportunity to pursue his dream. Cheng Dongqing, however, was rejected and stayed on as a university teacher. By 1988, Cheng Dongqing was married to Su Mei and giving private English lessons in addition to doing his university job. But when Su Mei left for the US after she got a visa, and Lucy returned home, Cheng Dongqing and Wang Yang were left alone. By 1992, China’s economy was starting to boom; but in the US, Meng Xiaojun, now married to Liang Qin, was fired from his job in a lab. The following year, Su Mei called Cheng Dongqing from the US and said she wanted to break up; subsequently, Cheng Dongqing was sacked from YJU’s Foreign Languages Faculty for his unauthorised private teaching. He and Wang Yang started a private school in an abandoned factory to feed the demand for English lessons and made a ton of money. In 1994, Meng Xiaojun returned from the US, with his tail between his legs, and joined the other two in the school, contributing his experience of what Americans want. They named the school New Dreams, moved into new premises and became the largest private school in China. But business differences between the three started to divide them.

REVIEW

Tapping directly into a contemporary Zeitgeist, as China flexes its muscles internationally and shows that anything the US has done it can do better, American Dreams in China 中国合伙人 couldn’t be more timely, its Mainland release coming only weeks after new president Xi Jinping 习近平 officially endorsed the “China Dream”. Though the subjects of the film by Hong Kong director Chen Kexin 陈可辛 [Peter Chan] are three university pals who get rich by teaching English to Chinese looking to study in the US, the movie is a de facto celebration of a whole generation of Mainland-born entrepreneurs who came of age during the 1980s and have since become world-calibre business leaders – especially go-getting, dotcom tycoons like Li Yanhong 李彦宏 [Robin Li], co-founder of search engine Baidu, Sohu founder Zhang Chaoyang 张朝阳 [Charles Zhang], plus others like Mao Daolin 茅道临 [Daniel Mao] and Ma Yun 马云 [Jack Ma], all of whom made their fortunes in traditionally US-dominated fields.

Though the movie is tailored directly to the China market – where it symbolically knocked Iron Man 3 (2013) off the top box-office spot – Chen brings his own, objective perspective to the subject-matter that speaks of his own background. Born in Hong Kong but raised in Thailand, he studied film at UCLA and briefly pursued his own American Dream in the late 1990s with the DreamWorks-produced rom-com The Love Letter (1998). After returning to Hong Kong, and pausing for a while as a director, he’s consistently worked on Mainland-set movies (Perhaps Love 如果•爱, 2005; The Warlords 投名状, 2007; Wu Xia 武侠, 2011) with an eye to the Greater China and international markets. For those who care to look for it, there’s a strong subtext to Dreams that shows the Mainland obsession with the US as a naive one, and one that is both unnecessary and bound to engender an aggressive response.

In the end, in what seems like an almost autobiographical speech by Chen put into the mouth of one of the protagonists, the three realise that they should pursue their dream in Chinese terms rather than as an ersatz version of another country’s “dream”. This message could be applied to the film itself, which would take some re-editing (and re-voicing of its English dialogue) to stand a chance of working in the US – and probably for no final benefit. Dreams is what it is, succeeds pretty well on its own terms, and has no need to curry to western taste.

In fact, the whole China-US theme, underlined by the film’s English-language title, is something of a red herring. The original title translates as “Chinese Partners” and, like most of Chen’s movies from his debut with Alan and Eric: Between Hello and Goodbye 双城故事 (1991), Dreams is a simple story of male friendship across the years. Especially in the first half, as the friends lark around at university and stumble towards their idea of an English language school, there’s a lot of the spirit (though not the Hong Kong tone) of Chan’s early roommate rom-com Tom, Dick, and Hairy 风尘三侠 (1992), though the friendship angle fights a running battle in the script with the career angle before the former finally takes precedence.

It’s not until some 90 minutes in that the issue of “never start a company with friends” is tackled head on, and the movie starts to work at a deeper emotional level. Till then, the sheer scope of the film – set across 20-odd years, on two continents, marking major events and cultural shifts, and centred on three men and their partners – doesn’t allow much time for the emotional core to develop, especially in a running time of under two hours. The clumsy framing device of the friends’ company being sued in the US for using stolen teaching materials acts as a further brake on the film’s organic development of the friendship theme, leading to a didactic speech (in awkward English) by the main protagonist whose content could have been more subtly conveyed in other ways and in a home setting.

Though it may not matter so much to Chinese-speaking audiences, the English dialogue is often ill-modulated, especially for characters who are meant to be teaching the language. Whether meant to be realistic, or a commentary on China’s language schools, it doesn’t work dramatically on screen, and voice doubles should have been used for the three lead actors in these sequences. Beyond that, the Chinese dialogue is natural and often very witty, and handled with brio by the players.

As the ambitious main protagonist, who dreams of going to the US and never coming back, Deng Chao 邓超 (Mural 画壁, 2011; The Four 四大名捕, 2012) powers the film in his strongest and most focused performance to date, modulated in different ways by Huang Xiaoming 黄晓明 (The Guillotines 血滴子, 2012; An Inaccurate Memoir 匹夫, 2012) and Tong Dawei 佟大为 (Great Wall My Love 追爱, 2011; The Flowers of War 金陵十三钗, 2011) as his less obviously driven pals. One of the film’s particular pleasures is how the three actors – almost unrecognisable as college friends, especially Tong with long locks – change facially over the years as middle age and business realities take their toll. Huang especially shines in the later stages, as he emerges as the true, cool businessman of the trio. Of the two actresses, ballet dancer-turned-model Du Juan 杜鹃, in her film debut, makes a graceful impression in the early stages, notably in a charmingly staged college romance with Huang’s character.

The photography by Christopher Doyle 杜可风 has a subtly textured appearance, with non-primary colours, that is just right for the scenes set in the 1980s and 1990s without overplaying a period look, and both art direction by Sun Li 孙立 and costume design by Hong Kong’s Wu Lilu 吴里璐 [Dora Ng] are spot on in their slightly heightened naturalism. A perky, attentive score by Jin Peida 金培达 [Peter Kam] helps to build mood and bind together the collage-like structure, while atmospheric use is made throughout of iconic songs, from Leaving on a Jet Plane to Chinese hits like the 1983 rock anthem The Same Moonlight 一样的月光 sung by Su Rui 苏芮 and the emotive 1987 ballad The World Outside 外面的世界 by Qi Qin 齐秦.

The film was reportedly inspired by the story of New Oriental School 北京新东方学校, founded by Beijing University English teacher Yu Minhong 俞敏洪 [Michael Yu] in 1993 and listed on the New York Stock Exchange in 2006. An opening credit notes that the film is adapted from an original script by Beijing Juben Production.

CREDITS

Presented by China Film (CN), We Pictures (HK). Produced by We Pictures (HK).

Script: Zhou Zhiyong, Zhang Ji. First draft screenplay: Lin Aihua [Aubrey Lam]. Photography: Christopher Doyle. Editing: Xiao Yang. Music: Jin Peida [Peter Kam]. Art direction: Sun Li. Costume design: Wu Lilu [Dora Ng]. Sound: Liu Yang, Wang Gang. US photography: Guan Zhiyao [Jason Kwan]. Executive director: Han Yi.

Cast: Huang Xiaoming (Cheng Dongqing), Deng Chao (Meng Xiaojun), Tong Dawei (Wang Yang), Du Juan (Su Mei), Wang Zhen (Liang Qin), Georg Anton (US consular officer), Daniel Berkey (Bonnard), Caitlin Fitzgerald (EES lawyer), Claire Quirk (Lucy), Tang Xiaofeng (history teacher), Yang Yi (policeman), Yang Chen (Li Ping), William Wu (Zhang Xi), Zhang Yuede (Gao, director), Liu Tianzuo (Niu Yongxiao), Mao Daqing (Mao Daqing), Tian Pujun (business leader), John Taylor (Oliver, teacher), Gong Cuiying (Cheng Dongqing’s mother), Yan Rui (rejected guy), Tong Lei (Xu Wen), Barbara Malley (restaurant lady), Tracey Ilgner (waitress), Catherine Gibson (EES receptionist), Anthony Santoro (New York taxi driver), Huang Wei (Meng Xiaojun’s grandfather), Lei Haowen (Meng Xiaojun, aged 6), Zhang Zimu (Liang Qin, aged 6), Huang Tianqi (Meng Xiaojun’s father), Kang Shengwen (Meng Xiaojun, aged 12), Lei Aijia (Liang Qin, aged 12), Allen Enlow (New Dreams lawyer), Bao Chenhui (Cheng Dongqing’s nephew), Liu Bin (village head), Feng Lun.

Release: China, 17 May 2013; Hong Kong, 30 May 2013.

(Review originally published on Film Business Asia, 30 May 2013.)