International Film Guide 1978

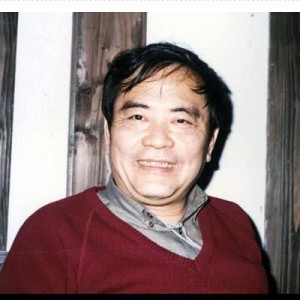

Director of the Year: Hu Jinquan [King Hu]

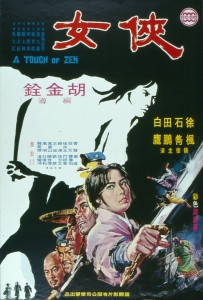

The triumphant passage of Hu’s A Touch of Zen 侠女 at Cannes in 1975, where it won the Grand Prix Technique [an award voted not by the competition jury but by France’s film & TV technicians’ association], set the seal of necessary, if spurious, respectability upon the Hong Kong/Taiwan film industry – an industry which had been flourishing far from western eyes for a decade already and which had exploded upon unsuspecting European and American markets approximately three years earlier in a welter of martial arts pictures. Hu’s output, as has become clear, lacks the raw energy and predatory ethics of mainstream (Mandarin-dialect) film-making and should not – like the works of many a nation’s artistic figureheads – be taken as representative of the whole; directors like Li Hanxiang 李翰祥, Zhang Che 张彻, Li Xing 李行, Chen Yaoqi 陈耀圻 [Richard Chen], Song Cunshou 宋存寿 or Liu Jiachang 刘家昌 work in more consciously modern Chinese terms. Hu’s success both at home and abroad is a tribute to his consummate skill in filtering a wide variety of influences: ineffably eclectic, steeped in loving scholarship, and with an abiding regard for both the achievement and modern relevance of the Chinese artistic/historical heritage, his films reach out to a wider audience through techniques reminiscent of a wide variety of sources – Peking Opera, traditional wushu, western masters from Michael Curtiz to Miklós Jancsó, and the Hong Kong mainstream. Unlike Zhang Che, Hu is concerned with the philosophic and mystical possibilities of the martial arts rather than simply their technique; like Zhang, however, he sees the lessons of history as changeless and immutable.

The triumphant passage of Hu’s A Touch of Zen 侠女 at Cannes in 1975, where it won the Grand Prix Technique [an award voted not by the competition jury but by France’s film & TV technicians’ association], set the seal of necessary, if spurious, respectability upon the Hong Kong/Taiwan film industry – an industry which had been flourishing far from western eyes for a decade already and which had exploded upon unsuspecting European and American markets approximately three years earlier in a welter of martial arts pictures. Hu’s output, as has become clear, lacks the raw energy and predatory ethics of mainstream (Mandarin-dialect) film-making and should not – like the works of many a nation’s artistic figureheads – be taken as representative of the whole; directors like Li Hanxiang 李翰祥, Zhang Che 张彻, Li Xing 李行, Chen Yaoqi 陈耀圻 [Richard Chen], Song Cunshou 宋存寿 or Liu Jiachang 刘家昌 work in more consciously modern Chinese terms. Hu’s success both at home and abroad is a tribute to his consummate skill in filtering a wide variety of influences: ineffably eclectic, steeped in loving scholarship, and with an abiding regard for both the achievement and modern relevance of the Chinese artistic/historical heritage, his films reach out to a wider audience through techniques reminiscent of a wide variety of sources – Peking Opera, traditional wushu, western masters from Michael Curtiz to Miklós Jancsó, and the Hong Kong mainstream. Unlike Zhang Che, Hu is concerned with the philosophic and mystical possibilities of the martial arts rather than simply their technique; like Zhang, however, he sees the lessons of history as changeless and immutable.

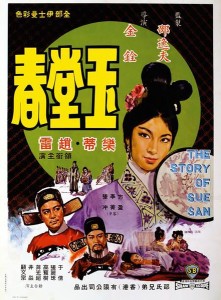

Hu Jinquan 胡金铨 [King Hu] was born in Beijing on 29 Apr 1931, the only son of an artist mother and mining engineer father. His upbringing, during which he read a great deal and travelled extensively in northern China, was within the confines of a large traditional feudal Chinese family (about 30 members) from whose tensions and internal struggles he tried unsuccessfully at one point to escape. Educated at Huiwen Middle School 汇文中学 and then at the Peking National Art College, Hu admits to considerable influence, given the restrictions of his close family, from his “democratic socialist” uncle; though far from antipathetic to the Communist takeover in 1949, he nonetheless found himself trapped in Hong Kong during a visit the following year, and it was thus there that he set about carving a career. After work as a journalist, artist and tutor, Hu was invited through personal  contacts first to become a set dresser and soon after an actor – the latter by veteran director Yan Jun 严俊, who later offered him the job of assistant director. During the 1950s Hu simultaneously built an acting career (frequently taking male ingenue roles), gained experience in directing, and worked in radio as a scriptwriter and producer. Yan’s other assistant had been Li Hanxiang and when Li joined Shaw Brothers’ new studio in the late 1950s he proposed Hu also, who joined up as an actor/scriptwriter. After working closely with Li (then Shaw’s premier director) for several years, he was entrusted [in 1963] with directing The Story of Sue San 玉堂春 (1964) – in fact, merely a clockwork realisation of Li’s scheme which involved no creative freedom (Hu now disowns the film).

contacts first to become a set dresser and soon after an actor – the latter by veteran director Yan Jun 严俊, who later offered him the job of assistant director. During the 1950s Hu simultaneously built an acting career (frequently taking male ingenue roles), gained experience in directing, and worked in radio as a scriptwriter and producer. Yan’s other assistant had been Li Hanxiang and when Li joined Shaw Brothers’ new studio in the late 1950s he proposed Hu also, who joined up as an actor/scriptwriter. After working closely with Li (then Shaw’s premier director) for several years, he was entrusted [in 1963] with directing The Story of Sue San 玉堂春 (1964) – in fact, merely a clockwork realisation of Li’s scheme which involved no creative freedom (Hu now disowns the film).

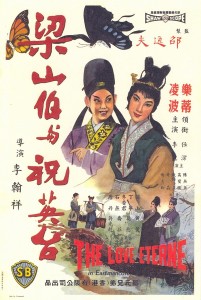

Hu’s official directing career had started the previous year with The Love Eterne 梁山伯与祝英台 (1963), a vastly successful film version of a traditional song-drama, a tragic love  story that traces the burgeoning romance between two young students in 4th century Zhejiang province, one of whom, Zhu Yingtai, is, unknown to the other, a girl disguised as a boy, the other of whom, Liang Shanbo, is played by an actress (Ling Bo 凌波 [Ivy Ling], quite remarkable in the role). Shooting on adjacent sound-stages and under great pressure, Li directed the more romantic sections between the two lovers and the graveyard finale in which their spirits rise from the grave as twin butterflies, while Hu (working largely from his own script improvised around the songs) directed roughly the remaining third – the “fast bits” in which the pupils journey to the college and the sequences within the classroom. Both directors manage to expand a classical and theatrical form in a way which is both thoroughly accessible and intensely cinematic, with Li’s stylishness and statuesque qualities acting as a foil to Hu’s thematic playfulness and lively wit.

story that traces the burgeoning romance between two young students in 4th century Zhejiang province, one of whom, Zhu Yingtai, is, unknown to the other, a girl disguised as a boy, the other of whom, Liang Shanbo, is played by an actress (Ling Bo 凌波 [Ivy Ling], quite remarkable in the role). Shooting on adjacent sound-stages and under great pressure, Li directed the more romantic sections between the two lovers and the graveyard finale in which their spirits rise from the grave as twin butterflies, while Hu (working largely from his own script improvised around the songs) directed roughly the remaining third – the “fast bits” in which the pupils journey to the college and the sequences within the classroom. Both directors manage to expand a classical and theatrical form in a way which is both thoroughly accessible and intensely cinematic, with Li’s stylishness and statuesque qualities acting as a foil to Hu’s thematic playfulness and lively wit.

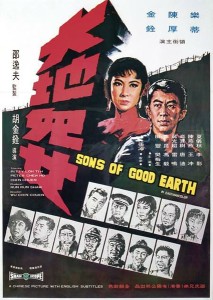

Sons of Good Earth 大地儿女 (1965) was Hu’s first solo attempt at direction. A large-scale depiction of Chinese guerrilla activity against the Japanese during World War II, it originally ran for three hours but was cut to 124 minutes by Shaws under pressure from new anti-racial laws passed in Singapore and Malaysia. Quite apart from being his only  “contemporary” picture to date [as of 1977], it is an intensely likeable film in its own right and boldly marks out the theme of collective rather than individual action to which Hu has remained uncompromisingly faithful ever since. Set in Wenchang county in northern China, it is divided into two parts, the first set in 1931 on the eve of the Japanese occupation, the second in 1937 as the occupiers begin to suffer reversals from Chinese resistance forces. Hu, working from his own script, concentrates on a small group of characters in a community, notably the young artist Yu Rui (finely played by Chen Hou 陈厚), his helper Guan Sansheng (Li Kun 李昆), and the young woman Hehua/”Lotus” (Le Di 乐蒂) whom they rescue from sale into concubinage. A wry introductory sequence rapidly delineates popular response to the increasingly tense political situation – with Hu’s bête noire, the intellectual singled out for the weakness “of large ideas and no action”. The wonder and magic lent the later films by the fight sequences here springs from those scenes in which a bland community reveals a rich solidarity as the covering layers are dramatically stripped away.

“contemporary” picture to date [as of 1977], it is an intensely likeable film in its own right and boldly marks out the theme of collective rather than individual action to which Hu has remained uncompromisingly faithful ever since. Set in Wenchang county in northern China, it is divided into two parts, the first set in 1931 on the eve of the Japanese occupation, the second in 1937 as the occupiers begin to suffer reversals from Chinese resistance forces. Hu, working from his own script, concentrates on a small group of characters in a community, notably the young artist Yu Rui (finely played by Chen Hou 陈厚), his helper Guan Sansheng (Li Kun 李昆), and the young woman Hehua/”Lotus” (Le Di 乐蒂) whom they rescue from sale into concubinage. A wry introductory sequence rapidly delineates popular response to the increasingly tense political situation – with Hu’s bête noire, the intellectual singled out for the weakness “of large ideas and no action”. The wonder and magic lent the later films by the fight sequences here springs from those scenes in which a bland community reveals a rich solidarity as the covering layers are dramatically stripped away.

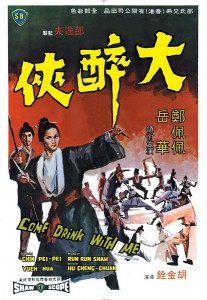

After censorship difficulties on Sons, and the abandonment [after two weeks’ shooting, about one-fifth completed] of a subsequent project designed to recoup production expenses by re-using the same materials [Ding Yishan 丁一山, the name of a guerrilla leader in Japanese-occupied China], Hu retreated to the safer ground of the period action  film which he has since made his own. Come Drink with Me 大醉侠 (1966) introduced for the first time the techniques of Peking Opera and music (Hu in collaboration with the actor Han Yingjie 韩英杰 – whose contribution to the martial arts boom has not been sufficiently acknowledged), and the film was an instant box-office success. It centres on the challenge offered by a ruthless gang led by the killer Jade-Face Tiger (Chen Honglie 陈鸿烈) to the due process of law as instrumented by the magistrate’s daughter Golden Swallow (a superlative performance from the dancer Zheng Peipei 郑佩佩, in a role she later repeated in Zhang Che’s [1968] film of the same name 金燕子) and the mysterious beggar Fan Dabei (Yue Hua 岳华, also at the beginning of his career) who finally falls in unequivocally with her. The story lacks the precise historical resonances of Hu’s other work and, as ever, he is temperamentally unwilling to explore the profound romanticism of the fateful pairing which Zhang was so successfully to realise, but the grace of the action sequences and the fluidity of the battle of wits played out with chess-like precision in the inn are thoroughly characteristic.

film which he has since made his own. Come Drink with Me 大醉侠 (1966) introduced for the first time the techniques of Peking Opera and music (Hu in collaboration with the actor Han Yingjie 韩英杰 – whose contribution to the martial arts boom has not been sufficiently acknowledged), and the film was an instant box-office success. It centres on the challenge offered by a ruthless gang led by the killer Jade-Face Tiger (Chen Honglie 陈鸿烈) to the due process of law as instrumented by the magistrate’s daughter Golden Swallow (a superlative performance from the dancer Zheng Peipei 郑佩佩, in a role she later repeated in Zhang Che’s [1968] film of the same name 金燕子) and the mysterious beggar Fan Dabei (Yue Hua 岳华, also at the beginning of his career) who finally falls in unequivocally with her. The story lacks the precise historical resonances of Hu’s other work and, as ever, he is temperamentally unwilling to explore the profound romanticism of the fateful pairing which Zhang was so successfully to realise, but the grace of the action sequences and the fluidity of the battle of wits played out with chess-like precision in the inn are thoroughly characteristic.

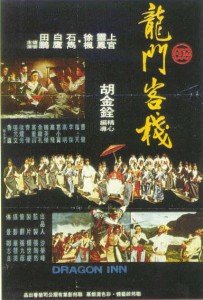

In 1965 Hu left Shaws and joined [Taiwan’s] Union Film Company as a director and production manager, building up the studio from scratch and hiring and training many actors and actresses who have since risen to prominence in the Hong Kong industry (like Bai Ying 白鹰, Xu Feng 徐枫, Mao Ying 茅瑛 [Angela Mao], Shangguan Lingfeng 上官灵风, Hu Jin 胡锦, Tian Peng 田鹏). Hu immediately set to work on what, after Come Drink with Me, was to form the second of his “inn trilogy” – the (Southeast Asia) record-breaking Dragon Inn 龙门客栈 (1967). The inn is a staple ingredient of the Chinese action film but  Hu’s use of its watering-hole qualities is consistently charged: here the inn is set amidst open, rock-strewn terrain, like some gigantic dried-up river-bed, and the kernel of the drama acted out during its quiet, off-season period. The inn functions both as a dramatic stage on which conflicts are played out and as a symbol of resistance to the ruthless suppression tactics of the Eastern Agency [aka Eastern Depot/Eastern Group/Eastern Chamber 东厂], the imperial Gestapo of the Ming dynasty (the film is set in AD 1457) controlled by the court eunuchs. Hu’s special gift for the pregnant, violence-charged calm before the storm – precariously balanced between humour and drama – is perfectly encapsulated in the early scene of the arrival of the stranger Xiao Shaozi (Shi Jun 石隽) as he slowly suspects the inn has been taken over by the agency: threatening pedals in the music, a blood stain on the table, and a comical go-between servant trying to serve him drugged wine are orchestrated with great assurance. Tension is maintained as both sides gather at the inn, loyalties are revealed and critical mass is reached – the final resolution played out high up in the mountains between Xiao and the all-powerful Cao Shaoqin (Bai Ying). In common with most of Hu’s finales the carefully built tempo becomes a little wayward, the plot-strands conventionally drawn together, but one can still appreciate the film’s great influence on the Hong Kong mainstream martial arts boom.

Hu’s use of its watering-hole qualities is consistently charged: here the inn is set amidst open, rock-strewn terrain, like some gigantic dried-up river-bed, and the kernel of the drama acted out during its quiet, off-season period. The inn functions both as a dramatic stage on which conflicts are played out and as a symbol of resistance to the ruthless suppression tactics of the Eastern Agency [aka Eastern Depot/Eastern Group/Eastern Chamber 东厂], the imperial Gestapo of the Ming dynasty (the film is set in AD 1457) controlled by the court eunuchs. Hu’s special gift for the pregnant, violence-charged calm before the storm – precariously balanced between humour and drama – is perfectly encapsulated in the early scene of the arrival of the stranger Xiao Shaozi (Shi Jun 石隽) as he slowly suspects the inn has been taken over by the agency: threatening pedals in the music, a blood stain on the table, and a comical go-between servant trying to serve him drugged wine are orchestrated with great assurance. Tension is maintained as both sides gather at the inn, loyalties are revealed and critical mass is reached – the final resolution played out high up in the mountains between Xiao and the all-powerful Cao Shaoqin (Bai Ying). In common with most of Hu’s finales the carefully built tempo becomes a little wayward, the plot-strands conventionally drawn together, but one can still appreciate the film’s great influence on the Hong Kong mainstream martial arts boom.

Buoyed by the success of Dragon Inn, Hu started production on A Touch of Zen (1970-73), an amplification of a short ghost story by the Ming scholar Pu Songling 蒲松龄. The main set, a ruined fort, took nine months to construct (and has since been used for innumerable other films, notably Song Cunshou’s Ghost of the Mirror 古镜幽魂, 1974) and, given other problems and Hu’s painstaking working method, took some two years to complete. In his absence the film was cut from three hours to two [for release in Hong Kong] and was a flop; Hu himself finally rescued it, and pieced together the complete version, shown for the  first time in 1975. [For the full story, see The Chronology of A Touch of Zen at the bottom of this review.] The film is the most extensive statement of his cinematic credo, as well as being the fullest expression of his interest in the clash of the real and supernatural in a philosophical context. The central figure of the young retiring scholar, Gu Shengzhai (Shi Jun), scraping a living from portrait painting between being nagged by his mother to marry and join the imperial civil service, is clearly dear to Hu’s own heart (as well as expressing the artistic devolution of the Ming era) and even in the film’s most fantastique moments, as Gu is unwittingly drawn into the elite universe of the main protagonists, this central portrait remains immensely human and well-observed (compare the similarly sympathetic portrait in Dragon Inn of the two young Tartars who tell the innkeeper of their dreams and aspirations when young of going to China). For the first hour Hu keep his audience in a state of suspended ignorance – his camera hypnotically tracking in long shot, with sudden flurries of intrigue and action bursting around our modest hero. The eventual welding of Gu’s scholarship with the martial skills of the fugitives from the Eastern Agency sets the scene for the first half’s confrontation – a booby-trapped fort recalling the empty, rigged Dragon Inn. The second half raises the conflict from the political to the philosophical as the game progresses to a showdown between the high priest Hui Yuan (the superb Qiao Hong 乔宏 [Roy Chiao], whose every twitch becomes a threat to existence) and the agency chief, Xu Xianchun (Han Yingjie, utterly demonic), with Gu and even the other protagonists reduced, in the film’s pyramidal structure, to the position of awed bystanders. As Hui Yuan achieves nirvana before the astonished eyes of the dying Xu, we, like Gu (as much pawns in Hu’s game as Gu was in theirs), receive a touch of zen, a tantalising, tangential experience of it, rather than the Buddhist blinding flash. Such is the measure of Hu’s achievement.

first time in 1975. [For the full story, see The Chronology of A Touch of Zen at the bottom of this review.] The film is the most extensive statement of his cinematic credo, as well as being the fullest expression of his interest in the clash of the real and supernatural in a philosophical context. The central figure of the young retiring scholar, Gu Shengzhai (Shi Jun), scraping a living from portrait painting between being nagged by his mother to marry and join the imperial civil service, is clearly dear to Hu’s own heart (as well as expressing the artistic devolution of the Ming era) and even in the film’s most fantastique moments, as Gu is unwittingly drawn into the elite universe of the main protagonists, this central portrait remains immensely human and well-observed (compare the similarly sympathetic portrait in Dragon Inn of the two young Tartars who tell the innkeeper of their dreams and aspirations when young of going to China). For the first hour Hu keep his audience in a state of suspended ignorance – his camera hypnotically tracking in long shot, with sudden flurries of intrigue and action bursting around our modest hero. The eventual welding of Gu’s scholarship with the martial skills of the fugitives from the Eastern Agency sets the scene for the first half’s confrontation – a booby-trapped fort recalling the empty, rigged Dragon Inn. The second half raises the conflict from the political to the philosophical as the game progresses to a showdown between the high priest Hui Yuan (the superb Qiao Hong 乔宏 [Roy Chiao], whose every twitch becomes a threat to existence) and the agency chief, Xu Xianchun (Han Yingjie, utterly demonic), with Gu and even the other protagonists reduced, in the film’s pyramidal structure, to the position of awed bystanders. As Hui Yuan achieves nirvana before the astonished eyes of the dying Xu, we, like Gu (as much pawns in Hu’s game as Gu was in theirs), receive a touch of zen, a tantalising, tangential experience of it, rather than the Buddhist blinding flash. Such is the measure of Hu’s achievement.

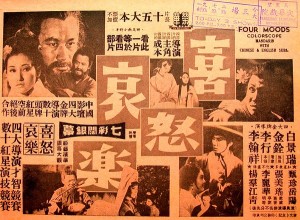

Before leaving Union in 1970, Hu contributed the [40-minute] episode Anger 怒 to the portmanteau Four Moods 喜怒哀乐 (1970), a voluntary production by a group of director friends [also including Taiwan’s Li Xing and Bai Jingrui 白景瑞] to rescue Li Hanxiang (temporarily independent of Shaws) from bankruptcy. [Based on the famous Peking Opera performance piece Crossroads/San cha kou 三岔口,] Anger is a footnote to the inn trilogy – a sustained cinematic fugue of

Before leaving Union in 1970, Hu contributed the [40-minute] episode Anger 怒 to the portmanteau Four Moods 喜怒哀乐 (1970), a voluntary production by a group of director friends [also including Taiwan’s Li Xing and Bai Jingrui 白景瑞] to rescue Li Hanxiang (temporarily independent of Shaws) from bankruptcy. [Based on the famous Peking Opera performance piece Crossroads/San cha kou 三岔口,] Anger is a footnote to the inn trilogy – a sustained cinematic fugue of  complex alliances formed, broken and exploited as officials from the Manchu Board of Punishment pause at an inn while conducting an obstreperous prisoner and become involved in a black marketeer ring. Anger has an easy, smooth pace, much quiet humour and an ironic ending with most of the cast dead from their own greed and the innkeeper’s sister (the splendid Hu Jin) loaded down like a pack-horse with the financial object of her desire.

complex alliances formed, broken and exploited as officials from the Manchu Board of Punishment pause at an inn while conducting an obstreperous prisoner and become involved in a black marketeer ring. Anger has an easy, smooth pace, much quiet humour and an ironic ending with most of the cast dead from their own greed and the innkeeper’s sister (the splendid Hu Jin) loaded down like a pack-horse with the financial object of her desire.

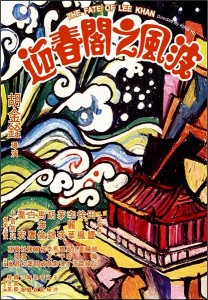

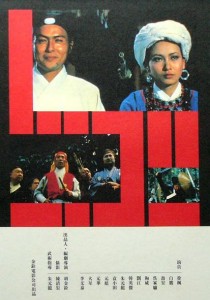

Hu has worked independently ever since the experience of A Touch of Zen at Union. From 1970 to 1973, in collaboration with Shaws’ major new rival Golden Harvest, he worked on his third “inn film” – and his masterpiece to date – The Fate of Lee Khan 迎春阁之风波 (1973). None of the other works quite so perfectly achieves that synthesis of movement  and flow which rests at the heart of all his works; none of them are quite so sensually colourful and costumed (Hu, accurate as ever, used genuine antiques for Lee Khan and his sister’s clothes). The film is set in AD 1366, near the end of the Yuan dynasty (1260-1368), when China was ruled by the invading Mongol hordes who had overthrown the Song. Lee Khan is at the very apex of this confused period, as the eponymous lord of Henan province arrives in neighbouring Shaanxi to collect a map of Chinese revolutionary plans acquired for him by a traitor. The inn acts as a dramatic stage on which to reflect the social and political turmoil of the period, with conventions every part as demanding as those of Greek tragedy – the action rarely strays outside, only the personnel changes. The film’s first section is a triumph of mood, a moto perpetuo of intrigue, comedy and everyday bustle only ever interrupted by the arrival of fresh guests: Hu’s camera tracks from table to table, cutting with perfect timing from thread to thread. The spectator is once again confused, the brew stirred to critical consistency, before the vital ingredient arrives in the form of Lee Khan and his lethal sister Wan’er (the misty-eyed Xu Feng, Hu’s most illustrious alumna, improving even on her charismatic performance in A Touch of Zen), with whom there ensues a life-and-death game of awesome skill and precision before the cards are finally laid on the table.

and flow which rests at the heart of all his works; none of them are quite so sensually colourful and costumed (Hu, accurate as ever, used genuine antiques for Lee Khan and his sister’s clothes). The film is set in AD 1366, near the end of the Yuan dynasty (1260-1368), when China was ruled by the invading Mongol hordes who had overthrown the Song. Lee Khan is at the very apex of this confused period, as the eponymous lord of Henan province arrives in neighbouring Shaanxi to collect a map of Chinese revolutionary plans acquired for him by a traitor. The inn acts as a dramatic stage on which to reflect the social and political turmoil of the period, with conventions every part as demanding as those of Greek tragedy – the action rarely strays outside, only the personnel changes. The film’s first section is a triumph of mood, a moto perpetuo of intrigue, comedy and everyday bustle only ever interrupted by the arrival of fresh guests: Hu’s camera tracks from table to table, cutting with perfect timing from thread to thread. The spectator is once again confused, the brew stirred to critical consistency, before the vital ingredient arrives in the form of Lee Khan and his lethal sister Wan’er (the misty-eyed Xu Feng, Hu’s most illustrious alumna, improving even on her charismatic performance in A Touch of Zen), with whom there ensues a life-and-death game of awesome skill and precision before the cards are finally laid on the table.

Hu’s latest film to date [1977], The Valiant Ones 忠烈图 (1975), lacks the unending resonances of Lee Khan but is never less than accomplished. The story of the struggle against Japanese pirates in 16th century Ming China is replete with the expected ebb and flow of artifice, suspicion and sylvan sussuration – Hu’s masterly skill at evoking a sense of dislocated reality, the pregnant calm which signals imminent danger, best seen in the forest attack in which Yu Dayou (Qiao Hong) silently signals his battle plan on a go board from a flautist’s information. And amongst both the inept Ming organisation and the pirates themselves Hu shows his perennial concern for the ruthlessly rigid pecking-order of power-structures – expressed, as always, through skill in the martial arts. The Valiant Ones may well mark a watershed in Hu’s remarkable development; his next moves will make fascinating viewing.

Hu’s latest film to date [1977], The Valiant Ones 忠烈图 (1975), lacks the unending resonances of Lee Khan but is never less than accomplished. The story of the struggle against Japanese pirates in 16th century Ming China is replete with the expected ebb and flow of artifice, suspicion and sylvan sussuration – Hu’s masterly skill at evoking a sense of dislocated reality, the pregnant calm which signals imminent danger, best seen in the forest attack in which Yu Dayou (Qiao Hong) silently signals his battle plan on a go board from a flautist’s information. And amongst both the inept Ming organisation and the pirates themselves Hu shows his perennial concern for the ruthlessly rigid pecking-order of power-structures – expressed, as always, through skill in the martial arts. The Valiant Ones may well mark a watershed in Hu’s remarkable development; his next moves will make fascinating viewing.

(Grateful acknowledgement to Verina Glaessner for her help in preparing this article and to Shaw Brothers in Hong Kong for kindly screening some of the films.)

(Article originally in UK annual International Film Guide 1978, published in Nov 1977. Modern annotations in square brackets. The other Directors of the Year in IFG 1978 were Claude Goretta, Vincente Minnelli, Michael Ritchie and Carlos Saura.)

Hu Jinquan: films as director

1963 The Love Eterne 梁山伯与祝英台 (as “executive director”; dir: Li Hanxiang 李翰祥)

1964 The Story of Sue San 玉堂春

1965 Sons of Good Earth 大地儿女

1966 Come Drink with Me 大醉侠

1967 Dragon Inn 龙门客栈

1970 A Touch of Zen 侠女上集

1970 Four Moods 喜怒哀乐 (second episode: Anger 怒; other episodes: Bai Jingrui 白景瑞, Li Xing 李行, Li Hanxiang)

1973 A Touch of Zen: Part Two 侠女下集 灵山剑影

1973 The Fate of Lee Khan 迎春阁之风波

1975 The Valiant Ones 忠烈图

1979 Raining in the Mountain 空山灵雨

1979 Legend of the Mountain 山中传奇

1981 The Juvenizer 终身大事

1983 All the King’s Men 天下第一

1983 The Wheel of Life 大轮回 (first episode; other episodes: Bai Jingrui, Li Xing)

1990 Swordsman 笑傲江湖 (co-dirs: Xu Ke 徐克 [Tsui Hark], Li Huimin 李惠民 [Raymond Lee], Cheng Xiaodong 程小东 [Tony Ching], Xu Anhua 许鞍华[Ann Hui], Jin Yanghua 金扬桦)

1993 Painted Skin 画皮 阴阳法王

Hu died on 14 Jan 1997, aged 65, in Taibei, following a heart operation earlier in the day.

D.E.