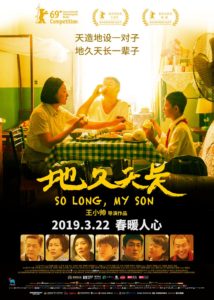

So Long, My Son

地久天长

China, 2019, colour, 1.85:1, 184 mins.

Director: Wang Xiaoshuai 王小帅.

Rating: 8/10.

Long-spanned saga of two families’ shared tragedy and denial is Wang Xiaoshuai’s masterwork to date.

A town in Inner Mongolia province, northern China, the mid-1980s. Liu Yaojun (Wang Jingchun) and Wang Liyun (Yong Mei), who work at the same government-owned factory, are distraught when their young son, Liu Xing, drowns in a swimming accident with some other boys by a reservoir. With him that day was his best friend Shen Hao, born on the same day to the couple’s close friends, Shen Yingming (Xu Cheng) and Li Haiyan (Ai Liya). (By the early 2000s, Liu Yaojun and Wang Liyun are living down south in a seaside town in northern Fujian province where he runs a repair shop and she mends fishing nets. They have an adopted son, now a teenager, to whom they gave the same name, Liu Xing, but he’s grown into a problem adolescent who hardly communicates with his parents and keeps skipping school. Things come to a head when he steals a walkman from another student; after Liu Yaojun scolds him, Liu Xing runs away from home.) In the 1980s, when both families lived in the factory dormitory and celebrated their sons’ birthday together, Wang Liyun became pregnant again and – because of the country’s one-child policy – tried to hide the fact, especially from Li Haiyan, who was a team leader at the factory. (Liu Xing has still not returned home. While putting a missing-person notice in the local paper, Liu Yaojun visits Shen Moli [Qi Xi], younger sister of Shen Yingming, who briefly worked under Liu Yaojun as an apprentice at the factory back home, is now divorced, and is planning to move to the US. She is in town on business and they meet at her hotel.) In the factory dormitory, the two families, plus friends Zhang Xinjian (Zhao Yanguozhang) and Gao Meiyu (Li Jingjing), who are almost a couple, hold a party at a time when there’s a government crackdown on “decadent” foreign music. Li Haiyan gets them to turn off a recording of Auld Lang Syne, a tune they all remember from the late 1970s in the wake of the Cultural Revolution. Subsequently Zhang Xinjian is arrested for organising a “lights-out” party and given a jail sentence. After learning of Wang Liyun’s pregnancy, Li Haiyan forces her to have an abortion, during which she haemorrhages heavily, preventing her having any more children. Feeling bad, Li Haiyan arranges for Liu Yaojun and Wang Liyun to receive the factory’s 1986 Family Planning Award. At a dance later on, Liu Yaojun is approached for a dance by Shen Moli, who has left the factory and is now at university. Subsequently, both families visit Zhang Xinjian in jail, and Gao Meiyu tells him she’s moving south to Guangzhou. Rumours circulate at the factory about forced lay-offs and at a rowdy meeting Wang Liyun’s name is among those selected. (Back in Fujian province, Shen Moli tells Liu Yaojun she has got her US visa, and also has some surprising news for him.) Then comes Liu Xing’s drowning, for which Shen Yingming and Li Haiyan blame their own son for letting it happen, while Liu Yaojun and Wang Liyun defend him, saying such accidents happen with children.

REVIEW

The fine run of films by Mainland director Wang Xiaoshuai 王小帅 since his renaissance with Chongqing Blues 日照重庆 (2010) reaches an apotheosis with So Long, My Son 地久天长, a three-hour saga set across some 30 years and centred on two families forever bound by a single tragedy. Precision cast and beautifully played in an unstarry way, it’s a film that drip-feeds the viewer with information as it swings back and forth between different eras, gradually building a web of ties and emotions that bind together a small group of friends as the country itself wipes out almost every physical trace of its recent past. Like several of Wang’s films, this one would also benefit from some tightening following its festival premiere; but even in the version unveiled at the 2019 Berlinale the film delivers a considerable emotional wallop in its final half-hour. Now 52, and after a quarter-century in the business, Wang has finally produced something close to a masterwork that discreet tightening by 15 or so minutes could rate a 9/10.

There’s no shortage of Chinese movies following families or friends across long spans of time, especially during the Mainland’s white-heat development into a market economy during the past 30-40 years. What makes My Son slightly different is that, though economic and social developments are always in the background, they’re not the main point of the film and (except by inference) are a cause for neither happiness nor regret. The long time-span is simply a device to show how the feelings of guilt and denial never die (per the Chinese title, a phrase meaning “for ever and ever”), even though some kind of closure is finally reached.

The film also isn’t a case of Wang jumping on the New vs Old China bandwagon that has fuelled so many sagas during the past couple of decades. My Son is full of themes from his earlier films, especially during his more mature period: notably Chongqing Blues (a father investigating his son’s mysterious death) but also 11 Flowers (shadows of the Cultural Revolution) and especially Red Amnesia (long-buried guilt). Like My Son, Amnesia also delivered emotionally in its final act after a somewhat discursive opening and development. And though set on a much broader stage, My Son even has links to Wang’s loose trilogy (Shanghai Dreams 青红, 2005; 11 Flowers 我11, 2011; Red Amnesia 闯入者, 2014) on families affected by the so-called Third Front 三线建设 movement of the 1960s, in which essential industries were relocated for national security. (Wang’s own upbringing was affected by this.)

That underlying theme of physical dislocation can be seen in the main couple’s move, during the 1980s, from their hometown in Inner Mongolia, northern China, to a southern coastal town – not because of any political movement but from state factory lay-offs dictated by the move towards a market economy and from the tragic death of their young son in a swimming accident. Liu Yaojun and his wife Wang Liyun, both average blue-collar workers, end up in a region (northern Fujian province) that feels like “another country”, where they don’t even understand the local dialect. They’ve also since adopted a son whom they’ve named after their dead one and who’s grown into a hostile, troubled adolescent who ends up running away from home after a major argument. Thrice abandoned (by their first son, adopted son, and northern roots), the couple seem to have nothing left except their own love for each other. Their past then impinges on their present, first via the visiting sister of Liu Yaojun’s best friend (who brings her own complications) and then by the news that the best friend’s wife (who partly caused their problems) is dying from dementia.

When the couple finally re-visit their hometown in the present day to set things right, they find the place is almost unrecognisable: as Wang Liyun says, “There’s no sign of our past” – apart from the decaying factory dormitory where they spent some of their happiest times during the late 1970s/early 1980s. Finally reconnecting with the other family, and learning the truth of their late son’s death, they have a traditional northern meal on their own, like exiles returning home, before a surprise development gives them a final chance for family happiness.

After so much grief, the quietly upbeat ending is a master stroke in the screenplay by A Mei 阿美 and Wang (from an original story by the latter). Wang’s scripts have been the weak element in some of his earlier movies but here everything works like clockwork, even as the film constantly switches time frames in a way that may be initially unclear for non-Chinese viewers (almost no hard dates, just vague references via artifacts and social developments). Gradually, however, it doesn’t matter for audiences prepared to go with the emotional flow. A Mei’s credits include co-writing the Cultural Revolution love story Under the Hawthorn Tree 山楂树之恋 (2010), and the more uneven portmanteau movie The Law of Attraction 万有引力 (2011) and rom-com/weepie A Wedding Invitation 分手合约 (2013); but outside movies, she’s written movingly about her own parents’ past deprivations, and in her Wang seems to have found the perfect collaborator for this particular story.

Performances and ensemble are pretty much flawless, quietly led by ever-dependable character veteran Wang Jingchun 王景春, 46 – the father in 11 Flowers; police chief in To Live and Die in Ordos 警察日记 (2013); Heaven’s gatekeeper in Beautiful Accident 美好的意外 (2017) – whose smiley-eyed features hide deep wells of disappointment and stubbornness – as well as, most tellingly, some emotional duplicity. He’s well partnered by TV actress Yong Mei 咏梅, 49, as his bruised but loyal wife, in a performance that travels organically from 1980s setbacks to a kind of knowing acceptance in the present. In the other family whose son shares the same birthdate, the heavy lifting is done by veteran Ai Liya 艾丽娅, 53 – like Yong actually of Inner Mongolian ethnicity – who’s come a long way from her career-defining role as the ambitious peasant wife in Ermo 二嫫 (1994), here investing the crucial role of the cadre-cum-friend with a complex mix of behaviour and emotions, climaxing in her powerful final scene.

In the supporting but keenly-etched role of her sister-in-law who has hidden feelings for the older Li Yaojun, dancer-turned-actress Qi Xi 齐溪, 34 – so good as the mistress in Mystery 浮城谜事 (2012) and spacey girlfriend in Ever Since We Loved 万物生长 (2015) – is standout, providing some of the film’s most resonant and subtle moments. As the rebellious adopted son, singer-actor Wang Yuan 王源, 18, doesn’t have much to do apart from look moody but fits the bill. In a late-on appearance, Du Jiang 杜江 has some moving moments as the dead son’s best pal, now grown into a doctor.

Packaging is quality all the way, without any distracting glossiness or even widescreen. In a curious decision, Wang, whose d.p. has generally been Wu Di 邬迪, has opted for South Korea’s Gim Hyeon-seok 김현석 (Poetry 시, 2010) who does a solid enough job but brings no extra texture to the film’s look. Occasional music by Dong Yingda 董颖达 (in her first major big-screen commission) is suitably low-key, with special emphasis on the tune Auld Lang Syne which encapsulates the film’s Chinese title. Art direction (by Lv Dong 吕东, Chongqing Blues, 11 Flowers) and costume design (by Pang Yan 庞燕, Wang’s Beijing Bicycle 十七岁的单车, 2001, plus Chongqing Blues) are all spot-on in an unshowy way. Ditto, the discreet ageing of the cast.

[On release in China, a month after its Berlinale premiere, the film flopped, taking a mere RMB45 million.] Though the characters’ hometown is never identified, shooting was in Baotou, Inner Mongolia province. For the record, the film’s Chinese title was previously used for two Hong Kong productions, the Early Republican melodrama Everlasting Love (1940) and HIV drama Forever and Ever (2001).

CREDITS

Presented by Dongchun Films (CN), Hehe Pictures (CN), FunShow Culture Communication (Beijing) (CN), Zhengfu Pictures (CN). Produced by Dongchun Films (CN).

Script: A Mei, Wang Xiaoshuai. Original story: Wang Xiaoshuai. Photography: Gim Hyeon-seok. Editing: Lee Chatametikool. Music: Dong Yingda. Art direction: Lv Dong. Costumes: Pang Yan. Sound: Qi Siming, Fu Kang. Visual effects: Guo Jiafu, Kei Nishiyama.

Cast: Wang Jingchun (Liu Yaojun), Yong Mei (Wang Liyun), Qi Xi (Shen Moli), Wang Yuan (Liu Xing), Du Jiang (Shen Hao), Ai Liya (Li Haiyan), Xu Cheng (Shen Yingming), Li Jingjing (Gao Meiyu), Zhao Yanguozhang (Zhang Xinjian).

Premiere: Berlin Film Festival (Competition), 14 Feb 2019.

Release: China, 22 Mar 2019.